- Keywords

- Deaccession, Settlement agreement/accord transactionnel, Artwork/oeuvre d’art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Due diligence, Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism, Spoils of war/butins de guerre, Procedural issue/limites procédurales, Negotiation/négociation, Cultural cooperation/coopération culturelle, Unconditional restitution/restitution sans condition, Ownership/propriété, Loan/prêt

Buddhist Paintings – Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism

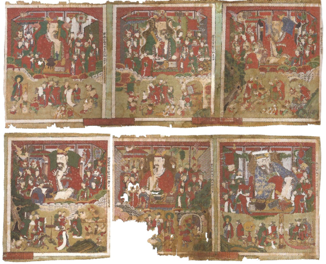

Siwangdo

Siwangdo

DOWNLOAD AS PDF – CASE NOTE IN ENGLISH

TELECHARGER LE PDF – AFFAIRE EN FRANCAIS

Citation: Naré G. Aleksanyan, Tessa C. DeJong, Alessandro Chechi, Marc-André Renold, “Case Buddhist Paintings – Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism”, Platform ArThemis (http://unige.ch/art-adr), Art-Law Centre, University of Geneva.

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) bought four Buddhist paintings in 1998. These paintings were featured in frequent exhibitions of LACMA’s Korean art galleries until the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism notified LACMA that the paintings were stolen. After amicable negotiation, these paintings were returned to the Jogye Order.

I. Chronology

Spoils of war

- October 1954: Army troops of the United States (US) stole the Buddhist painting “Yeongsanhoesangdo”[1] and three sections of the “Siwangdo” scrolls[2] (hereinafter “Buddhist Paintings”) at the end of the Korean War. It is not known to whom or where they were transported initially.

- 1998: The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) purchased the Buddhist Paintings from Mary S. French after she discovered them rolled up and severely damaged in the attic of her son’s house in Hopkinton, New Hampshire.[3] This was the first time these items had appeared since the end of the Korean War and very few people even knew they existed.[4]

- 2015: The Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism (hereinafter “Jogye Order”) approached LACMA and presented evidence that seven paintings in the museum’s collection were stolen, including the Buddhist Paintings.[5]

- August 2020: LACMA returned the Buddhist Paintings to the Jogye Order.[6]

II. Dispute Resolution Process

Negotiation – Settlement agreement

- Following notification that they were in possession of stolen paintings, LACMA examined the evidence presented by the Jogye Order. LACMA conducted their own research as well.[7]

- LACMA curators Stephen Little and Virginia Moon traveled to Sinheung Temple in order to verify the legitimacy of the photographs presented as evidence. They did this by standing in the same locations from which the photographs were taken. They also met with the local priest to discuss the provenance of the paintings.[8]

- The dispute resolution process here can be characterized as a very amicable period of research and investigation on both sides, with each side working hard to confirm the evidence.

III. Legal Issues

Deaccession – Due Diligence – Ownership – Procedural issue/limites procédurales

- When claims of theft or disputed ownership arise, evidence is crucial. Both the Jogye Order and LACMA agreed that the circumstantial evidence was credible and clearly established the theft of the paintings from South Korea. As such, no formal legal processes needed to be employed in order to further confirm provenance and legal title.

- The due diligence process was largely through cooperation and with evidence provided by the Jogye Order, which primarily included US Army photographs of the Main Buddha Hall and the Hall of Jijang Bodhisattva. This evidence showed the paintings had been removed from the original temple. The first set of photographs conveyed the paintings’ presence in late May/June of 1954. Additional photographs from October 1954 reflected the paintings’ disappearance. The Jogye Order also presented facts supporting that the US Army completely controlled the entire area surrounding the Sinheung Temple, only a few kilometers from the demilitarized zone.[9]

- LACMA began the deaccession process of these four paintings following its curators’ investigations and recommendation to the Board of Trustees (“Board”) for deaccession. Composition of LACMA’s bylaws encourage approval of all recommendations in light of fiduciary duty standards for boards.[10] Before deaccession is recommended to the Board, it must receive the approval of the directors and curators of the museum, which protects the Board from potential legal liability by aligning itself with the directors and curators to act per their recommendation for what is in the museum’s best interest. Had the Board disagreed with the recommendation, and the museum endured a costly lawsuit, questions of fiduciary duty could arise as well, which would especially be of concern to Board members where the state of the law on fiduciary standards for non-profits is in flux.[11]

- LACMA protocol differs for each case of disputed art, but generally consists of assessing external evidence as well as doing their own independent research to ensure the evidence is reliable. In this situation, LACMA’s internal investigations led to the conclusion that the photographic evidence was reliable. LACMA bylaws also require a 3 month waiting period and unanimous approval of the board before a decision on deaccession is made.[12] In fiduciary duty claims, the court focuses on “the care and diligence with which the decision was made, not the decision itself”.[13] These bylaws appear to speak to that standard and attempt to shield board members and the museum from potential liability.

- Their willingness to recommend deaccession may stem from an earlier confiscation of Korean Royal Seals taken during the Korean War. In that case, before the museum announced restitution willingly, a US Homeland Security official related that the department confiscated the seals from the museum after South Korea asked the US government to investigate how the seals ended up in the LACMA.[14] One could imagine that the LACMA hoped to avoid similar embarrassment with respect to the Buddhist Paintings.

IV. Adopted Solution

Cultural cooperation – Loan – Unconditional restitution

- LACMA recognized the Jogye Order’s title to the Buddhist Paintings and returned the works to South Korea in August 2020. The works were reinstalled in the Sinheung Temple.[15]

- In response to LACMA’s acknowledgment and support of Korean cultural preservation efforts, the Jogye Order will participate in art loan exchange programs and collaborative educational programs with LACMA. As of the date of this writing, however, there is currently not an exchange program planned due to the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic.

V. Comment

- This case is unique for its straightforward resolution. It is also notable as a current reflection of a new trend in art restitution absent a civil lawsuit, as well as of a larger call to decolonize museums.[16] In the context of war, the case for systematic restitution is even stronger. It is especially significant in the Korean War, where there was widespread public resistance to US involvement in the first place.

- The return of South Korean artifacts marks a departure from the US’s historical approach towards South Asian art, specifically South Korean art. In the past, US repatriation efforts of South Asian art followed a hierarchy with Japan at the top. Even the Monuments Men run by the US Military, whose mission was to return plundered artifacts, made no attempt to recover Korean War era artworks and return them to South Korea.[17]

- The recognition of South Korean claims to plundered art mirrors the rise of South Korean art more generally. Although there is relatively little South Korean art in the US compared to other Asian art, the US’s reparation of South Korean art may allow for increased loans and exchange programs, which will allow South Korean art to receive more public and academic attention.[18]

- The state of law on fiduciary duties for non-profits may also be at play here, especially considering the possibility of holding their boards to a stricter standard in the future.[19] Here, because LACMA’s and directors both recommended to the Board that the paintings be returned, if the Board did not comply with their request it could potentially face breach of fiduciary duty claims. The vocal social media opposition to this could also be a real factor to consider since LACMA would then be at a significant risk of losing money as a result of such public condemnation. Conversely and as was the case here, overwhelmingly positive responses were seen on social media to LACMA’s action, which also demonstrates a general public consensus in support of cultural repatriation.[20] These responses may also signal a shift in public tolerance for museums’ and private collectors’ retention of art where there is questionable title history. LACMA’s willingness and cooperation led to collaborative efforts going forward which benefit public, academic as well as institutional interests in preserving and promoting cultural patrimony.

VI. Sources

a. Bibliography

- Art Review. “LACMA Returns Buddhist Paintings Looted During Korean War.” Art Review. 9 July 2020. Accessed 28 July 2020. https://artreview.com/lacma-returns-buddhist-paintings-looted-during-korean-war/.

- Keener, Katherine. “Art World Roundup: Art Acquisitions, Art Restitution, and the End of King Tut’s Touring Show?” Art Critique. 10 July 2020. Accessed 13 August 2020. https://www.art-critique.com/en/2020/07/art-world-roundup-from-acquisitions-to-a-king-tut-exhibition/.

- Kim, Christine. “Colonial Plunder and the Failure of Restitution in Postwar Korea.” Journal of Contemporary History. 2017. Accessed 18 October 2020. https://www.academia.edu/33836772/Colonial_Plunder_and_the_Failure_of_Restitution_in_Postwar_Korea.

- Chen, Sue. “Art Deaccessions and the Limits of Fiduciary Duty.” Duke Law Scholarship Repository. 2009. Accessed 11 October 2020. https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1001&context=studentpapers.

b. Media

- Artnet News. “The Los Angeles County Museum of Art Restituted Four Buddhist Paintings Looted by Americans During the Korean War.” Artnet News. 8 July 2020. Accessed 26 July 2020. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/lacma-restituted-buddhist-paintings-south-korea-1893046.

- Little, Stephanie, and Moon, Virginia. “LACMA Repatriates Buddhist Treasures to Korea.” LACMA. 1 July 2020. Accessed 26 July 2020. https://unframed.lacma.org/2020/07/01/lacma-repatriates-buddhist-treasures-korea.

- Korea Bizwire. “Joseon Dynasty-era Buddhist Paintings to Return Home from U.S.” Korea Bizwire. 25 June 2020. Accessed 28 July 2020. http://koreabizwire.com/joseon-dynasty-era-buddhist-paintings-to-return-home-from-u-s/163053.

- Korea JoongAng Daily. “Joseon Dynasty-era Buddhist Paintings to Return Home from U.S.” Korea JoongAng Daily. 25 June 2020. Accessed 28 July 2020. https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2020/06/25/culture/koreanHeritage/Joseon-Dynasty-Buddhist-paintings-return-home/20200625182900270.html.

- LACMA. “LACMA Repatriates Buddhist Treasures to Korea.” LACMA Instagram. 1 July 2020. Accessed 28 July 2020. https://www.instagram.com/p/CCHDjtylV-d/.

- Panero, James. “Korean Culture Is on the Rise. What about Korean Art?” National Endowment for the Humanities. July/August 2014. Accessed 18 October 2020. https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2014/julyaugust/feature/korean-culture-the-rise-what-about-korean-art.

- Tse, Fion. “LACMA Repatriates Korean Buddhist Paintings.” Art Asia Pacific. 10 July 2020. Accessed 28 July 2020. http://artasiapacific.com/News/LACMARepatriatesKoreanBuddhistPaintings.

- Weber, Christopher and Kim, Hyung-Jin. “Los Angeles Museum Gains Painting, Could Lose Seal.” 27 November 2012. Access 11 October 2020. https://www.timesofisrael.com/los-angeles-museum-gains-painting-could-lose-seal/.

- Useum. “Six of the Ten Kings of Hell.” Useum. Accessed 13 August 2020. https://useum.org/artwork/Six-of-the-Ten-Kings-of-Hell-Anonymous.

[1] The painting “Yeongsanhoesangdo” (“Preaching Shakyamuni Buddha”) was commissioned in 1755 during the 31st year of King Yeongjo’s reign. It depicts Buddha preaching sutra. The painting, which is the earliest hanging scroll painting from Gangwon Province in existence today, and is regarded as a masterpiece due to its size (335.2 x 406.4 cm) and prominent artistic style, hung behind the altar in the back of the “Daeungjeon” (“Main Buddha Hall”). Author’s personal archives (press release shared via email by Jogye Order, 11 August 2020).

[2] The “Siwangdo” (“Kings of Hell”) scrolls were commissioned in 1798 during the 22nd year of King Jeongjo’s reign and were enshrined in “Myeongbujeon” (“Hall of Jijang Bodhisattva”), where they hung behind each of the ten Kings of Hell. These three scrolls depicted six of the ten Kings of Hell. Worshippers often prayed to these paintings for guidance from hell to paradise as well as for health, longevity and fortune. Useum, “Six of the Ten Kings of Hell.” Author’s personal archives (press release shared via email by Jogye Order, 11 August 2020).

[3] Artnet News, “The Los Angeles County Museum of Art Restituted Four Buddhist Paintings Looted by Americans During the Korean War.”

[4] Author’s personal archives (telephone communication with Stephen Little, curator, Virginia Moon, curator, Pamela Kohanchi, counsel, and Nancy Thomas, Senior Deputy Director of LACMA, 13 August 2020).

[5] Artreview, “LACMA Returns Buddhist Paintings Looted During the Korea War.”

[6] See supra n. 4; the other three paintings in question were returned to the Jogye Order in 2017, see Little and Moon, “LACMA Repatriates Buddhist Treasures to Korea.”

[7] Keener, “Art World Roundup: Art Acquisitions, Art Restitution, and the End of King Tut’s Touring Show?”

[8] Author’s personal archives (telephone communication with Stephen Little, curator, Virginia Moon, curator, Pamela Kohanchi, counsel, and Nancy Thomas, Senior Deputy Director of LACMA, 13 August 2020).

[9] Ibid.

[10] Chen, “Art Deaccessions and the Limits of Fiduciary Duty.”

[11] Ibid., at 131.

[12] Ibid., at 131, fns. 172 and 173.

[13] Ibid., at 138.

[14] Weber and Kim, “Los Angeles Musuem Gains Painting, Could Lose Seal.”

[15] Korea JoongAng Daily,“Joseon Dynasty-era Buddhist Paintings to Return Home from the US.”

[16] Tse, “LACMA Repatriates Korean Buddhist Paintings.”

[17] Christine Kim, “Colonial Plunder and the Failure of Resitution in Postwar Korea,” 607, 624.

[18] Panero, “Korean Culture is on the Rise. What about Korean Art?”

[19] Chen, “Art Deaccessions and the Limits of Fiduciary Duty. ”

[20] LACMA Instagram, “LACMA repatriates Buddhist treasures to Korea.”

Document Actions