- Keywords

- Unconditional restitution/restitution sans condition, Judicial claim/action en justice, Conciliation, Hans Sachs, Foundation German Historical Museum, Procedural issue/limites procédurales, Archives, Judicial decision/décision judiciaire, Nazi looted art/spoliations nazies, Ownership/propriété, Negotiation/négociation

Poster Collection – Sachs Heirs v. Foundation German Historical Museum

The posters have been taken from the catalogue of the exhibition "Kunst! Kommerz! Visionen!".

DOWNLOAD AS PDF – CASE NOTE IN ENGLISH

TELECHARGER LE PDF – AFFAIRE EN FRANCAIS

Citation: Marius Müller, Alessandro Chechi, Marc-André Renold, “Poster Collection – Sachs Heirs v. Foundation German Historical Museum,” Platform ArThemis (http://unige.ch/art-adr), Art-Law Centre, University of Geneva.

Hans Sachs, a Jewish dentist, began collecting posters from the end of the nineteenth century. This collection was considered lost as a result of its seizure by the Nazis in 1937 and the turmoil caused by the Second World War. In 2005, Peter Sachs, as Hans Sachs’ son and sole heir, located his father’s collection at the German Historical Museum and demanded its restitution. Unsuccessful conciliation was followed by a lawsuit. A judgment of the German Federal Court of Justice of March 2012 made possible the return of the poster collection to Peter Sachs.

I. Chronology

Nazi-looted art

- 1914: Hans Sachs, a Jewish dentist, presented his collection of 700 posters at the “International Exhibition of the Book Industry and Graphic Arts” at Leipzig.[1]

- March 1937: Sachs organized an exhibition at the Jewish Museum in Berlin. Shortly afterwards his collection was seized on instruction of Joseph Goebbels.[2]

- 1938: Sachs was arrested, deported to Sachsenhausen concentration camp, and shortly afterwards released. He then fled to the United States with his family, leaving behind his collection of about 12.500 posters.[3]

- 1961: Believing the collection to be lost, Sachs claimed compensation according to the procedure set forth in the Federal Restitution Act. A compensation of 225.000 DM was paid by the Federal Republic of Germany.

- 1963: Eberhard Hoelscher informed Hans Sachs that a part of his collection was stored in the Museum for German History of East Berlin (which later became the German Historical Museum).[4]

- 1966: In a letter, Hans Sachs articulated he would not be interested in a material way in the collection that re-emerged in the Museum for German History.[5]

- 1981: A significant part of the collection was stolen from the Museum for German History.[6]

- 2005: Peter Sachs, Hans Sachs’ son and sole heir, began investigating the whereabouts of the collection,[7] and located them at the German Historical Museum (Deutsches Historisches Museum – the former Museum for German History). Following unsuccessful negotiations, the parties resorted to the “Advisory Commission on the Return of Cultural Property Seized as a result of Nazi Persecution, especially from Jewish Possession” (hereinafter “Advisory Commission”) of the Federal Republic of Germany.[8]

- June 2006: Peter Sachs registered more than 4.000 posters in the “Lost Art Internet Database”.[9]

- 25 January 2007: The Advisory Commission issued a recommendation in favour of the German Historical Museum.

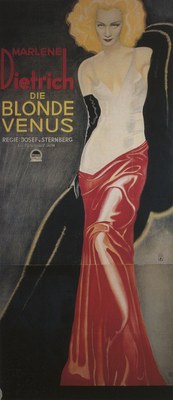

- March 2008: Peter Sachs filed lawsuit in the Berlin District Court against the Foundation German Historical Museum[10] to recover the possession of two posters “Die Dogge” (Great Dean) and “Blonde Venus” (Blond Venus).[11] Alternatively, he demanded to be declared the owner of the collection.

- February 2009: The Berlin District Court ruled that the German Historical Museum had to return the poster “Die Dogge”. The claim for the “Blonde Venus” and the counterclaim were denied.

- 28 January 2010: The Berlin Appellate Court declared – following the defendant’s alternative claim – that Peter Sachs was not entitled to claim restitution of the collection and denied the remaining claims.[12]

- 16 March 2012: The German Federal Court of Justice reversed by rejecting the Foundation’s counterclaim. Consequently, Peter Sachs was allowed to claim the restitution of the entire poster collection.

II. Dispute Resolution Process

Negotiation – Conciliation – Judicial claim – Judicial decision

- Between Hans Sachs and the West German Federal Government – In 1961, Hans Sachs received 225.000 DM from the West German Federal Government on the basis of the Federal Restitution Act. It is unclear why Sachs did not claim restitution after the collection re-emerged in 1963. It can be submitted that he had refrained from filing a lawsuit against the Museum for German History of East Berlin because of the belief that it would have been hopeless given the tension existing at the time between West and East Germany.

- Between Peter Sachs and the German Historical Museum – During the initial negotiations, Peter Sachs was confident that the German Historical Museum would have returned the collection voluntarily. However, as negotiations proved unsuccessful, the parties resorted to the conciliation of the Advisory Commission. It was Bernd Neumann, the then Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media, that suggested to call for the Advisory Commission to propose a settlement to Peter Sachs and the German Historical Museum.[13] The Advisory Commission’s recommendation was rendered on 25 January 2007.[14] Based on a letter of 1966, which was regarded as containing the will of Hans Sachs, the Commission recommended to leave the collection with the German Historical Museum. In particular, the Commission emphasised that Sachs had wished that his collection was made available to the public at large in a reputable museum.

- As he was disappointed with the recommendation, in March 2008 Peter Sachs brought legal action against the Foundation German Historical Museum before the Berlin District Court in order to obtain the restitution of his father’s collection. From there the disputed case reached the German Federal Court of Justice.

III. Legal Issues

Ownership – Procedural issues

- Ethical rules, the Principles adopted on the occasion of the Washington Conference on Holocaust-Era Assets (hereinafter “Washington Principles”)[15] – Although non-binding, the Washington Principles impose upon nations a moral commitment to identify and publicize stolen artworks and to assist their return to their original owners. However, the German Historical Museum rejected the claim that it had an obligation under the Washington Principles, because these would only apply to “not identifiable” works of art, that is, lost to the precedent owner in the post-war turmoil. In the Museums’ opinion, the poster collection could not be considered “not identifiable” since 1963.

- Conciliation process – The Washington Principles called on States to establish “[c]ommissions or other bodies […] to identify art that was confiscated by the Nazis and to assist in addressing ownership issues” (Principle 10) and to take steps “expeditiously to achieve a just and fair solution, recognizing this may vary according to the facts and circumstances surrounding a specific case” (Principle 8). The Advisory Commission was created in Germany to implement these principles.[16] This Commission can take non-binding recommendations concerning the restitution of contested items on moral or ethical grounds, for instance by referring to the circumstances of the loss, the fate of the former owners, and the level of effort in claiming back the looted materials. As such, it can play the role of mediator or conciliator,[17] in the spirit of the Washington Principles and of the “Common Declaration of the German Federal Government, the Länder and the municipal representatives” of 1999.[18] With this “Common Declaration” the signatories committed to verify the provenance of cultural objects in their possession and to return the pieces that had been looted during the Second World War, especially from Jewish owners.

- The Advisory Commission’s recommendation was based on a letter sent by Hans Sachs to a staff member of the Museum for German History of East Berlin in 1966. In this letter, Hans Sachs wrote: “For 28 years I had to assume my poster collection to have disappeared completely, which I brought together during 40 years […] approximately one month ago I received a totally different massage from Dr Hoelscher from Munich. I have to give full credence to it as you have to understand and as I expected nothing less as this massage that gave me certainty, that it would succeed to preserve at least parts of this irretrievable treasure for the general public […] from the beginning I would like to accentuate explicitly that I am not at all interested in a material way in this cooperation but only in a non-material way. After several years of negotiation, I received some time ago by means of a German court order a higher compensation, which covered all my claims. Of course this compensation could not compensate my non-material loss, which will not heal until the end of my life”.[19] This wording was considered as a renunciation of the collection by Hans Sachs.

- With its judgment of February 2009, the Berlin District Court decided that the poster “Die Dogge” had to be returned to Peter Sachs as he was the legal successor of Hans Sachs. In the Court’s opinion, the collection’s seizure by the Gestapo in 1938 caused only Hans Sachs’ loss of possession but not of its ownership title. The judgment was based on Section 985 of the German Civil Code (BGB).[20] The Court considered inapplicable the Property Act in the instant case mainly because: (i) Hans Sachs had received a compensation in 1961 following the agreement concluded with the West German Federal Government; (ii) neither Hans Sachs nor his legal successors had lost ownership title to the poster collection at any time.[21]

- The Berlin Appellate Court overruled the decision of the Berlin District Court on the ground that cases relating to crimes committed during the Nazi regime should not be resolved on the basis of general civil law provisions, including Section 985 BGB, but on the basis of existing special post-war legislation. On the other hand, the Appellate Court rejected the restitution claim pursuant to Section 242 BGB[22] and on the basis of Hans Sachs’ correspondence and pronouncements. The Court also referred to judgments from the early 1950s in which the preclusive effect of Allied compensation legislation had been affirmed.[23]

- In March 2012, the Federal Court of Justice (Fifth Chamber for Civil Matters) overruled the judgment of the Appellate Court and ordered the return of the poster collection to Peter Sachs. The Federal Court’s decision was based on Section 985 BGB and on the following arguments.

- First, Article 51, sentence 1, of the Restitution Decree of the Allies for West-Berlin does not preclude the restitution of the poster collection given that the pecuniary compensation received by Hans Sachs was considered a subsidiary form of redress, restitution in rem being the preferred solution. In other words, the Federal Court decided that the sum received by Hans Sachs could not be regarded as a final redress because the collection disappeared after the war and re-emerged after the expiration of the registration deadline for restitution claim.[24]

- Second, the Federal Court ruled that the restitution claim was not barred according to Sections 985 and 242 BGB as stated by the Court of Appeal. In particular, the Court maintained that a general renunciation to property rights on the part of Hans Sachs could not be implicitly deduced but should result from an unambiguous behaviour. Therefore, the reference to the compensation in his correspondence could not be considered an express renunciation to his rights to the collection. The Federal Court also underlined that claiming restitution from a public museum in the former German Democratic Republic in the Cold War period was probably a hopeless enterprise.

- Finally, the Federal Court of Justice affirmed that the failure of Hans Sachs’ successors to demand restitution of the collection is not sufficient to reject Peter Sachs’ claim.[25] In this respect, the expiry of the time period specified in Section 30a (1), sentence 1, of the Property Act would not have created a legitimate expectation of the museum to be no longer exposed to a claim for restitution. Claims for restitution according to Sections 3 and 6, or claims for compensation according to Sections 6 (7) and 8 of the Property Act could not be asserted in regard to movable goods after 30 June 1993.

IV. Adopted Solution

Unconditional restitution

- With its judgment of March 2012, the Federal Court of Justice established that the owner of a work of art which was lost due to Nazi persecution can be returned to the rightful owner pursuant to the general rule of German civil law (Section 985 BGB), provided that the owner was unable both to trace his/her property in the aftermath of the Second World War and to file a restitution claim under existing Allied legislation.

- Hence, the Foundation German Historical Museum was finally obliged to restitute the remaining part of the collection of Hans Sachs to Peter Sachs.

V. Comment

- 1. On the evolution of German Compensation Law doctrine – With the 2012 judgement of the German Federal Court of Justice civil law claims for the restitution of Nazi looted cultural assets are no longer precluded by special Compensation Laws. The case of the Hans Sachs poster collection shed light on the evolution of German law and jurisprudence regarding cultural property seized during the Nazi regime.[26] After 1945 German courts tried to resolve cases of such assets by applying general civil law. This raised numerous legal difficulties. In most of the cases it was impossible to find satisfying solutions by means of the application of the German Civil Code.[27] Despite the demand for a single German compensation legislation, the political circumstances in post-war Germany led to the adoption of several Restitution Laws[28] in the different occupied zones by the Allied administrations since 1947. Later this legislation was completed by the West-German legislator.

- To guarantee legal security it was held until the 1950s that claims related to Nazi confiscated assets should be solved exclusively by applying these special laws. The doctrine of the preclusive effect was born. In this context, even the United States Court of Restitution Appeals in Nuremberg decided in 1951[29] that the loss of right would be definitive, in case the limitation, established by the Restitution Law for the US Zone, for filing claims had expired.

- However, with the special Restitution Laws the application of prevailing civil law claims was not explicitly regulated.[30] Already in 1955 the doctrine of preclusive effect was disputed. Deciding on a case of Nazi persecution, the Federal Court of Justice found that a claim for restitution could be filed, although the restitution procedure had not been initiated before the prescribed time limits.[31] Here lies the origin of the differing considerations of the Berlin District and the Appellate Court.

- Consequently, two doctrines conflicted in regard to the case of the Sachs poster collection. On the one hand there was the argument that time limits established by Restitution Laws underlined the necessity to guarantee legal stability in the first post-war decade, which was considered necessary by the Allies. On the other hand, the historic reading of this legislation was reconsidered. German laws dealing with the consequences of the Nazi regime are tied to the legal-philosophical duty of complete compensation.[32] Therefore, the preclusive effect has been rejected by scholars in recent literature[33] and this argumentative line was confirmed by the 2012 judgment of the German Federal Court of Justice.

- 2. On the 2012 Judgement – The Federal Court of Justice articulated a fundamental principle: in case of a re-emergence of a cultural asset a preclusive effect would exclude the victim of Nazi injustice and his/her legal successors permanently from the primary objective of compensation, which is the restitution in rem. This cannot be seen as the adequate application of the regulations of the special restitution legislation and ethical standards (e.g. the Washington Principles).[34] It would mean to perpetuate the injustice in cases in which restitution would be legally possible.

- The Federal Court of Justice did not deal with an important issue, as it did not resolve the question whether the Foundation could have been allowed – based on the “Common Declaration” – to claim the forfeiture according to Section 242 BGB.[35]

- However, in this case it is not clear why the Federal Court of Justice denied the forfeiture of the claim for restitution under Section 242 BGB in this specific case. The claim for restitution was not asserted for a significant period of time. It was in 2006 when Peter Sachs claimed restitution although his father knew about the collection’s remaining in the last 40 years. Thanks to the German Historical Museum, Hans Sachs’s life work was publically acknowledged and preserved. His poster collection was presented as the elementary part of a special exhibition and as a doubtlessly decisive piece of European and German History of Art, Culture and Customs.[36] This unique collection as “treasure” that should be accessible entirely to the general public in the opinion of Hans Sachs has already been auctioned to over have its pieces.[37]

- 3. A fair solution in the light of Washington Principle 10? – The conciliation process by the “Advisory Commission” was initiated after Peter Sachs’ lawyer contacted the Federal Government Commissioner Bernd Neumann.[38] However, the vote of this Commission, the first in favour of a public entity, was not accepted by Peter Sachs. It might be asked if the following lawsuits were the adequate and “fair” solution. The solution envisaged in its recommendation by the “Advisory Commission” might have been the best legal compromise for both parties.

- In the end, this case illustrates the continuing political and social awareness regarding the moral obligations Germany still faces with regard to National Socialist history and looted works of art.

VI. Sources

a. Bibliography

- Anton, Michael, Rechtshandbuch Kulturgüterschutz und Kunstrestitutionsrecht, Vol. 1 - 3 Internationales Kulturgüterprivat- und Zivilverfahrensrecht, Berlin/New York: De Gruyter, 2010.

- Busche, Jan, “Zur Frage des Verhältnisses von Vermögensgesetz und allgemeinem Zivilrecht,” JuristenZeitung 2 (1994): 100-102.

- Deutsches Historisches Museum, Kunst! Kommerz! Visionen! Deutsche Plakate 1888-1933, Berlin: Edition Braus, 1993.

- Götz, Schulze, “Die Washington Principles und die Restitution der Plakatsammlung Sachs, Anmerkung zu Kammergericht v. 28.1.2010, Az. 8 U 56/09,“ KunstRechtsSpiegel (KunstRSp) 1 (2010): 9-12.

- Hartung, Hannes, Kunstraub in Krieg und Verfolgung. Die Restitution der Beute- und Raubkunst im Kollisions- und Völkerrecht, Berlin: De Gruyter Recht, 2005.

- Hartung, Hannes, “Die Restitution der Raubkunst in Europa. Eine Rechtsvergleichende Bestandsaufnahme,” in Eine Debatte ohne Ende? Raubkunst und Restitution im deutschsprachigen Raum, ed. Julius Schoeps, Anna-Dorothea Ludewig, (Berlin: Verlag für Berlin-Brandenburg: 2007), 155-188

- Jayme, Erike, “Narrative Normen im Kunstrecht,“ in Recht im Wandel seines sozialen und soziologischen Umfelds, Festschrift für Manfred Rehbinder, ed. Jürgen Becker München/Bern: C.H. Beck/Stämpfli, 2002.

- Müller-Katzenburg, Astrid, “Besitz- und Eigentumssituation bei gestohlenen und sonst abhanden gekommenen Kunstwerken,” Neue Juristische Wochenschrift 35 (1999): 2251-2558.

- Raue, Peter, “Summum ius suma inuria: Stolen Jewish Cultural Assets under Legal Examination,” in Art and Cultural Heritage – Law, Policy and Practice ed. Barbara T. Hoffman, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006, 185-190.

- Roemer, Walter, “Comment of on the decision of the KG on the 29 October 1946,” Süddeutsche Juristenzeitung (SJZ) II (1947): 263-267.

- Rudolph, Sabine, Restitution von Kunstwerken aus jüdischem Besitz – Dingliche Herausgabeanspürche nach deutschem Recht, Berlin: De Gruyter Recht, 2007.

- Sachs, Hans, “Wie meine Plakatsammlung entstand,” Die Reklame 20 (1927): 68.

- Sachs, Hans, “Die künstlerischen und kulturellen Werte einer Plakatsammlung,” Gebrauchsgrphik 1 (1931): 57.

- Weller, Matthias, “Kein Ausschluss des allgemein-zivilrechtlichen Anspruchs auf Herausgabe nach § 985 BGB durch das Rückerstattungsrecht,” KunstRSp 1 (2009): 41-45.

b. Court decisions

- BGH, “Naturalrestitution vor Rückerstattungsanordnung – Plakat ‘Dogge’, Urteil vom 16.3.2012,” Neue Juristische Wochenschrift 25 (2012): 1796-1800. English translation is available at: http://www.commartrecovery.org/docs/Decision%20of%20the%20Federal%20Court%20of%20Justice_16%20March%202012_V%20ZR%20279_10_translation.pdf

- “LG Berlin, Urteil vom 10.02.2009, Az. 19 O 116/08. Zum Verhältnis von Bundesrückerstattungsgesetz, Vermögensgesetz und zivilrechtlichen Ansprüchen”, Kunst und Recht 2 (2009): 57-64.

- “KG Berlin, Urteil vom 28. Januar 2010, 8 U 56/09. Herausgabeanspruch bei NS-verfolgungsbedingt abhanden gekommenen Sachen“, Kunst und Recht 1 (2010): 17-21.

- BGH, “Enteignung einer Versicherungsforderung gegen ein im Inland zugelassenes ausländisches Versicherungsunternehmen,” Neue Juristische Wochenschrift 15 (1953): 542-545.

- BGH, “Ausschließlichkeit der REGe,” Neue Juristische Wochenschrift 51/52 (1953): 1909-1910.

- BGH, “Bedeutung und Rechtsfolgen der Verfallerklärung auf Grund § 3 der 11. DVO RBürgerG,” Neue Juristische Wochenschrift 24 (1955): 905-907.

c. Legislation

- West German Federal Indemnification Law (Bundesentschädigungsgesetz or BEG) of 1952.

- Restitution Decree of the Allies for West-Berlin (REAO).

- Federal Restitution Act (Bundesrückerstattungsgesetz or BRückG).

- Property Act (Gesetz zur Regelung offener Vermögensfragen vor VermG).

- German Civil Code (BGB).

d. Documents

- “Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art 1998.” Accessed October 25, 2016. http://www.state.gov/p/eur/rt/hlcst/122038.htm.

- “Zweite Empfehlung der Beratenden Kommission für die Rückgabe NS-verfolgungsbedingt entzogener Kulturgüter”. Accessed 25 October 2016, https://www.kulturgutverluste.de/Content/06_Kommission/DE/Empfehlungen/07-01-25-Empfehlung-der-Beratenden-Kommission-im-Fall-Sachs-DHM.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=6.

- “Erklärung der Bundesregierung, der Länder und der kommunalen Spitzenverbände zur Auffindung und zur Rückgabe NS-verfolgungsbedingt entzogenen Kulturgutes, insbesondere aus jüdischem Besitz.” Accessed 25 October 2016, http://www.lostart.de/Content/01_LostArt/DE/Downloads/Handreichung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4.

- Press release of Peter Sachs’ lawyers. Accessed 25 October 2016, http://www.lootedart.com/web_images/news/Sachs%20Press%20Release.%202-18-10.pdf.

- Federal Court of Justice press release Nr. 39/2012. Accessed 25 October 2016, http://www.lootedart.com/web_images/pdf/Bundesgerchtshof%20document.py.html.

e. Media

- von Pufendorf, Ludwig and Ulrice Michelbrink, “Hans Sachs’ Plakatsammlung dem Deutschen Historischen Museum abgesprochen – ein gefährliches Fehlurteil.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, November 14, 2011. Accessed 25 October 2016. http://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/staat-und-recht/hans-sachs-plakatsammlung-herausgabe-um-jeden-preis-11960653.html.

- Kahn, Eve M. “Posters Lost to Nazis Are Recovered, and Up for Sale,” The New York Times, 17 October 2013. Accessed 15 October 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/18/arts/design/posters-lost-to-nazis-are-recovered-and-up-for-sale.html.

[1] This collection was completed with an index by artist name and topics depicted. Sachs, “Wie meine Plakatsammlung entstand”; and Deutsches Historisches Museum, Kunst! Kommerz! Visionen! Deutsche Plakate 1888-1933, 19, 20-22.

[2] Deutsches Historisches Museum, ibid., p. 22.

[3] Anton, Rechtshandbuch Kulturgüterschutz und Kunstrestitutionsrecht, Vol. 3, p. 303 ff.

[4] Deutsches Historisches Museum, supra note 1, 23.

[5] Translation by the author. The original reads as follows: “Von vornherein moechte ich ausdruecklich betonen, dass ich materiell ueberhaupt nicht an einer solchen Zusammenarbeit interessiert bin, sondern lediglich ideell”, ibid., 25.

[6] Ibid., 25.

[7] Press release of Peter Sachs’ lawyers, accessed October 25, 2016, available at: http://www.lootedart.com/web_images/news/Sachs%20Press%20Release.%202-18-10.pdf.

[8] Beratende Kommission im Zusammenhang mit der Rückgabe NS-verfolgungsbedingt entzogener Kulturguts, insbesondere aus jüdischem Besitz, also known as the “Looted Art Commission” or “Limbach-Commission”. Established in 2003 by the German Government, the Advisory Commission “can be called upon to mediate in cases of dispute involving the restitution of cultural assets which were confiscated during the Third Reich, especially from persecuted Jewish citizens and are now held by museums, libraries, archives or other public institutions in the Federal Republic of Germany. The Commission can mediate between the institutions which manage the collections and the former owners or heirs of the cultural goods, if desired by both sides. It can also offer recommendations for settling differences of opinion”.

[9] Available at: http://www.lostart.de/Webs/EN/LostArt/Index.html. This database registers cultural objects which were relocated, moved or seized (especially from Jewish owners) as a result of Nazi persecution. It is operated by the German Lost Art Foundation and is funded by the Federal Republic of Germany and the Länders.

[10] The German Historical Museum, which was founded as a limited company (GmbH), became a Foundation under public law in 2008.

[11] “LG Berlin, Urteil vom 10.02.2009, Az. 19 O 116/08. Zum Verhältnis von Bundesrückerstattungsgesetz, Vermögensgesetz und zivilrechtlichen Ansprüchen”, Kunst und Recht, 2 (2009): 57-64.

[12] “KG Berlin, Urteil vom 28. Januar 2010, 8 U 56/09. Herausgabeanspruch bei NS-verfolgungsbedingt abhanden gekommenen Sachen”, Kunst und Recht, 1 (2010): 17-21.

[13] On the functions of the Advisory Commission see supra note 8.

[14] “Zweite Empfehlung der Beratenden Kommission für die Rückgabe NS-verfolgungsbedingt entzogener Kulturgüter”, accessed 25 October 2016: https://www.kulturgutverluste.de/Content/06_Kommission/DE/Empfehlungen/07-01-25-Empfehlung-der-Beratenden-Kommission-im-Fall-Sachs-DHM.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=6.

[15] On the initiative of the United States, the conference took place in December 1998 in order to find a general solution to the problem of the cultural assets looted by the Nazis.

[16] Similar bodies have been established in France, the Netherlands, Austria, and the United Kingdom.

[17] See supra note 8.

[18] “Erklärung der Bundesregierung, der Länder und der kommunalen Spitzenverbände zur Auffindung und zur Rückgabe NS-verfolgungsbedingt entzogenen Kulturgutes, insbesondere aus jüdischem Besitz”, accessed 25 October 2016: http://www.lostart.de/Content/01_LostArt/DE/Downloads/Handreichung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4.

[19] Translation by the author. The original reads as follows: “28 Jahre lang habe ich annehmen muessen, dass meine Plakatsammlung, die ich in 40 jaehrigem Sammeln zusammengetragen hatte, voellig vom Erdboden verschwunden war [...] Vor etwa einem Monat erhielt ich von Herrn Dr. Hoelscher aus München eine völlig andere Nachricht, der ich vollen Glauben schenken musste, obwohl, wie Sie verstehen werden, ich alles andere eher erwartet hatte, als diese Nachricht, die mir die Gewissheit geben wuerde, dass es gelungen waere, wenigstens einen Teil dieser unwiederbringlichen Kostbarkeit für die Allgemeinheit zu erhalten [...] Von vornherein moechte ich ausdruecklich betonen, dass ich materiell ueberhaupt nicht an einer solchen Zusammenarbeit interessiert bin, sondern lediglich ideell. Nach mehrjaehrigen Verhandlungen habe ich schon vor einiger Zeit durch einen deutschen Gerichtsbeschluss eine groessere Abfindungssumme ausgezahlt bekommen, die alle meine Ansprüche gedeckt hat. Selbstredend war die Abfindungssumme nicht im Stande, meinen ideellen Verlust unfehlbar zu machen, der bis an mein Lebensende nicht vernarben wird”, Deutsches Historisches Museum, supra n. 1.

[20] Claim for restitution: “The owner may require the possessor to return the thing”.

[21] LG Berlin, supra n. 11.

[22] Performance in good faith: “An obligor has a duty to perform according to the requirements of good faith, taking customary practice into consideration”.

[23] BGH, “Enteignung einer Versicherungsforderung gegen ein im Inland zugelassenes ausländisches Versicherungsunternehmen,” Neue Juristische Wochenschrift 15 (1953): 542-545; BGH, “Ausschließlichkeit der REGe,” Neue Juristische Wochenschrift 51/52 (1953): 1909-1910.

[24] BGH, “Naturalrestitution vor Rückerstattungsanordnung – Plakat ‘Dogge’”, Neue Juristische Wochenschrift 25 (2012): 1798.

[25] BGH, “Plakat Dogge”, 1798-1799.

[26] On this see Anton, Rechtshandbuch Kulturgüterschutz, p. 489 ff.; Hartung, “Die Restitution der Raubkunst in Europa. Eine Rechtsvergleichende Bestandsaufnahme”.

[27] Roemer, “Comment of on the decision of the KG on the 29 October 1946”. He also demanded special laws that could prevent the absolute legal fragmentation by court decisions.

[28] “Law 59” of 10 November 1947 in the American Zone; “VO 120” of 10 November 1947 for the French Zone; and the “REAO” of 27 July 1949 for West Berlin. This body of legislation has to be considered related to civil law: Anton, Rechtshandbuch Kulturgüterschutz und Kunstrestitutionsrecht, Vol. 1 (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2010), 492, 497.

[29] United States Court of Restitution Appeals for the American Zone was established in Nuremberg in 1954 to decide on the restitution of property taken by Nazi. Court reports are available here: http://hls.harvard.edu/library/digital-collections-and-exhibitions/court-of-restitution-appeals-reports/.

[30] Schulze, “Die Washington Principles”, 10.

[31] Vid. BGH, “Bedeutung und Rechtsfolgen der Verfallerklärung auf Grund § 3 der 11. DVO RBürgerG,” Neue Juristische Wochenschrift 24 (1955): 905-907.

[32] Weller, “Kein Ausschluss des allgemein-zivilrechtlichen Anspruchs auf Herausgabe nach § 985 BGB durch das Rückerstattungsrecht”.

[33] Hartung, Kunstraub in Krieg und Verfolgung; Rudolph, Restitution von Kunstwerken aus jüdischem Besitz.

[34] Jayme, “Narrative Normen im Kunstrecht”.

[35] BGH, “Plakat ‘Dogge’” 1799.

[36] An evaluation of Hans Sachs formulated in 1931: “In front of us a contemporary, cultural and artistic document appears, which allows deep insight into the people and the nation. Who collects posters carries out history of art, culture and customs”, cf. Sachs, “Die künstlerischen und kulturellen Werte einer Plakatsammlung”.

[37] Kahn, “Posters Lost to Nazis Are Recovered, and Up for Sale”.

[38] Pufendorf and Michelbrink, “Hans Sachs’ Plakatsammlung dem Deutschen Historischen Museum abgesprochen – ein gefährliches Fehlurteil”.

Document Actions