- Keywords

- Deaccession, Judicial decision/décision judiciaire, State responsibility/responsabilité internationale des Etats, Italy/Italie, Archaeological object/objet archéologique, Judicial claim/action en justice, Colonialism/colonialisme, Unconditional restitution/restitution sans condition, Negotiation/négociation, Libya/Libye, Settlement agreement/accord transactionnel, Inalienability/inaliénabilité

Venus of Cyrene – Italy and Libya

|

|

|---|

DOWNLOAD AS PDF - CASE IN ENGLISH

TELECHARGER LE PDF - AFFAIRE EN FRANCAIS

Citation: Alessandro Chechi, Anne Laure Bandle, Marc-André Renold, “Case Venus of Cyrene – Italy and Libya,” Platform ArThemis (http://unige.ch/art-adr), Art-Law Centre, University of Geneva.

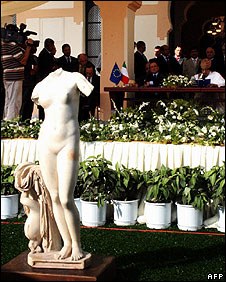

In 1913, Italian soldiers deployed at Cyrene, Libya, found a headless marble sculpture, commonly known today as the “Venus of Cyrene”. In 1915, the statue was shipped to Italy, where it was placed on display in the Museo Nazionale delle Terme of Rome. The Venus was returned to Libya in August 2008, following lengthy negotiations and two court decisions.

I. Chronology

Colonialism

- 1911: Italy declared war on the Ottoman Empire on 29 September and formally annexed the territories of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica with Royal Decree No. 1247 of 5 November 1911. The Ottoman Empire capitulated only a year later, when it agreed to close the hostilities with the Peace Treaty of Ouchy of 18 October 1912.[1] However, the recognition of the Italian sovereignty over Libya by the European Powers occurred only with the Peace Treaty of Lausanne of 24 July 1923, whereas it was not until 1932 that all of Libya was placed under Italian control.[2]

- 28 December 1913: Italian troops found by chance a headless marble sculpture representing the goddess Venus in the Greek settlement of Cyrene.[3]

- 1915: The statue, a Roman copy of a Greek original, was shipped to Italy for safekeeping, as there was no suitable repository to ensure the safeguarding of the statue from the ongoing military activities caused by the resistance of the local population.[4]

- 1947: Following the fall of the Axis Powers, Italy relinquished all claims to Libya with the Peace Treaty of 1947. Libya declared its independence on 24 December 1951.

- 1989: Libyan authorities requested the restitution of the Venus of Cyrene for the first time.

- 1998: Negotiations culminated in the Joint Communiqué of 4 July 1998, which concerned, inter alia, the restitution of all cultural assets removed from the former Italian colony.

- 2000: Italy and Libya concluded an Agreement on the restitution of the Venus of Cyrene.

- 1 August 2002: The Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities passed a decree to implement the 1998 Joint Communiqué and the 2000 Agreement. The ministerial decree acknowledged that Italy no longer had interest in owning the claimed statue and authorized its removal from the State patrimony and its restitution to Libya.

- 14 November 2002: Italia Nostra, an Italian non-governmental organisation, filed a lawsuit before the Tribunale Amministrativo Regionale (“TAR”, i.e. the Regional Administrative Tribunal) of Lazio against the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities seeking the annulment of the decree of 1 August 2002. The start of the lawsuit prevented the return of the Venus.

- 28 February 2007: The TAR rejected Italia Nostra’s claim and upheld the decree, confirming that Italy was under an obligation to return the Venus of Cyrene to Libya on the basis of both the 1998 Joint Communiqué and the 2000 Agreement.[5] Italia Nostra appealed the judgment before the Consiglio di Stato (“Council of State”).

- 23 June 2008: The Consiglio di Stato upheld the judgment of the TAR.[6]

- 30 August 2008: The Venus of Cyrene was returned to Libya.[7]

II. Dispute Resolution Process

Negotiation – Settlement agreement – Judicial claim – Judicial decision

- Since 1989, when the restitution of the Venus of Cyrene was firstly requested, Italy and Libya were committed to settling this issue through bilateral negotiations. However, given the numerous issues left unsettled after the end of the Italian colonial occupation and the ups and downs in Italian-Libyan relations,[8] negotiators had to first resolve other problems before discussing the fate of the statue. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that the Joint Communiqué of 1998 contained the apologises of the Italian Government for the suffering caused to the Libyan people as a result of Italian colonization and, in addition, pledged to start a new era of friendly and constructive relations. Moreover, it envisaged a wide inter-State cooperation in the sectors of trade, industry, energy, defence, disarmament, the fight against terrorism and illegal immigration.

- With the Joint Communiqué of 1998, the Italian Government committed to return “all manuscripts, archives, documents, artefacts and archaeological pieces transferred to Italy during and after the Italian occupation of Libya in accordance with the UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Cultural Property”.[9] In addition, the two countries agreed to “cooperate to determine these manuscripts, documents, artefacts and archaeological pieces and their whereabouts”.[10] However, as said, the question of the restitution of the Venus of Cyrene was resolved through the Agreement that resulted from the first meeting of State representatives of 11-13 December 2000. In order to implement the 1998 Joint Communiqué and the 2000 Agreement, on 1 August 2002 the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage passed a decree. This acknowledged that Italy no longer had interest in owning the claimed statue and authorized its removal from the State patrimony and restitution to Libya.[11]

- The lawsuit filed by Italia Nostra against the Ministry of Cultural Heritage hindered the immediate return of the Venus and threatened the success of the negotiations. As said, Italia Nostra sought the annulment of the decree of 1 August 2002. The claim was grounded on the premise that the artwork in question was a component of Italian cultural heritage because it had been discovered in territory subject to Italian sovereignty. As such, it could be removed from the patrimony of the State and ceded to a foreign sovereign only with the enactment of a specific law, and not by way of a mere governmental decree. Next, the plaintiff lamented that the decree was illegitimate because the Ministry did not take into account the artistic and cultural value of the sculpture. Italia Nostra argued that the proper setting for the Venus was the Italian heritage and not the patrimony of an Islamic country. Further, Italia Nostra pointed out that the cession of the statue could create a precedent likely to cause further requests for restitution and the consequent impoverishment of the Italian patrimony.[12]

III. Legal Issues

Deaccession – Inalienability – State responsibility

- The instant case involved multiple legal issues such as: (i) the legitimacy of the restitution of the Venus of Cyrene in light of the national rules prohibiting the deaccessioning of items forming part of the Italian patrimony, which is, by definition, inalienable; and (ii) the responsibility of the Italian State arising from the removal of the statue during the colonial occupation of Libya. The Italian Government resolved these issues by undertaking to return the Venus of Cyrene as well as all other “manuscripts, archives, documents, artefacts and archaeological pieces transferred to Italy during and after the Italian occupation of Libya”.[13]

- As far as the issue of State responsibility is concerned, it is worth noting that by undertaking the return of the Venus, the Italian Government abided by the principle of international law according to which the commission of a wrongful act – such as the subjugation of people through military occupation – involves an obligation to make reparation in order to re-establish the situation which existed before the wrongful act was committed. The restitution of property wrongly seized is the first remedy available to a State as a result of a breach of the prohibition of the use of force. It is only when restitution is impossible or inadequate that States may resort to other forms of reparation, including restitution in kind, compensation, and apology.

- Still with regard to the issue of State responsibility, the TAR ruled that Italy was obliged to return the statue to Libya on the basis of the 1998 Joint Communiqué and the 2000 Agreement. The Tribunal not only found that such bilateral agreements were valid and binding, but also that they reiterated obligations already incumbent upon the Italian State under customary law. In particular, the TAR referred to the customary rule that sanction the reconstitution of national cultural patrimony through the restitution of the works of art removed during military occupation and colonial rule, as manifested in Article 56 of the Regulations with respect to the Laws and Customs of War on Land, annexed to the Hague Convention (II) with respect to the Laws and Customs of War on Land of 29 July 1899, Article 46 of the Regulations Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, annexed to Hague Convention (IV) Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land of 26 January 1910, and Article I of the First Protocol to the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict of 14 May 1954.

- The Consiglio di Stato improved upon the reasoning of the TAR. It established that the international obligation compelling the restitution of cultural objects taken wrongfully in times of war or colonial occupation was the corollary of the interplay between two principles of general international law, namely the principle prohibiting the use of force – enshrined in Article 2, paragraph 4, of the Charter of the United Nations – and the principle of self-determination of peoples – enshrined in Articles 1, paragraph 2, and 55 of the Charter of the United Nations. The Consiglio di Stato explained that the principle of self-determination of peoples had come to include the cultural identity as well as the cultural heritage linked either to the territory of a sovereign State or to peoples subject to a foreign government. Consequently, the restitution of works of art served the safeguarding of such cultural ties whenever these have been jeopardized by acts of war or the use of force arising from colonial domination.

- With respect to the problem of inalienability, the Consiglio di Stato affirmed that the ministerial decree of 2002 reflected a binding international obligation and hence it prevailed over conflicting domestic rules, even if formally hierarchically superior, including the norms prohibiting the deaccessioning of cultural objects belonging to the State patrimony. For the same reason, it rejected the Italia Nostra’s contention that the removal of the statue from the patrimony of the State necessitated the enactment of a specific law.

IV. Adopted Solution

Unconditional restitution

- The Venus was returned on 30 August 2008, when the then Italian Prime Minister flew to Benghazi to sign the Treaty on Friendship, Partnership and Cooperation between Italy and Libya. The Treaty was meant to put an end to Libya’s claims relating to Italian colonialism. It contained a condemnation of Italian colonialism as well as the terms of the compensation for the damages caused by colonization. In this context, the restitution of the Venus of Cyrene represented a “complete and moral acknowledgement of the damage inflicted on Libya by Italy during the colonial era”.[14]

V. Comment

- The return of the Venus of Cyrene to Libya should be seen as an important development for at least three reasons. First, because it was sanctioned by two innovative court decisions that shed light on the controversial issue of the return of cultural objects taken away during colonialism. Second, because the return of the Venus served as an expedient to protect and enhance the financial, political and trade relations between Libya and Italy. Third, because it may be seen as a further endorsement of the campaign pursued by the Italian Government against the illicit trafficking in cultural objects and towards the recovery of works of art. This campaign has led to the conclusion of bilateral agreements with important market States and with a number of museums and has resulted in the restitution of numerous masterpieces.[15] Indeed, had it not returned the Venus, Italy’s campaigning would have appeared hypocritical.[16]

- As far as the court decisions are concerned, it should be acknowledged that such judgments are not free from flaw – though the TAR and the Consiglio di Stato did not err in pointing out that Italy was under an obligation to return the Venus. In particular, it is necessary to recall that the TAR and the Consiglio di Stato affirmed the legitimacy of the restitution of the Venus proceeding from the premise that the territory where the statue was discovered was not under Italian sovereignty at the relevant time and that, therefore, the Venus has never become part of the inalienable patrimony of the State.[17] More specifically, the Consiglio di Stato excluded that the sculpture had been subject to the regime set forth by Royal Decree No. 1271/1914 – which established that all antiquities discovered in the colonies had to be vested in the patrimony of the State – given that it entered into force nearly one year after its discovery. Consequently, neither the TAR nor the Consiglio di Stato realized the inherent contradiction in affirming, at the same time, that the Venus did not belong to the inalienable patrimony of the State and that the ministerial decree authorizing its declassification from the Italian patrimony and its restitution was legitimate![18]

VI. Sources

a. Bibliography

- Chechi, Alessandro. “The Return of Cultural Objects Removed in Times of Colonial Domination and International Law: The Case of the Venus of Cyrene.” Italian Yearbook of International Law (2008): 159-181.

- Laroui, A. “African Initiatives and Resistance in North Africa and the Sahara.” In General History of Africa, VII, Africa under Colonial Domination 1880-1935, edited by Albert Adu Boahen, 87-113. Paris: UNESCO, 1985.

- Ronzitti, Natalino. “Sugli obblighi di restituzione la sentenza amministrativa non convince.” Guida al diritto-Il Sole 24 Ore 21 (2007): 100-103.

- Wilkie, Nancy C. “Colonization and Its Effect on the Cultural Property of Libya.” In Cultural Heritage Issues: The Legacy of Conquest, Colonization, and Commerce. Edited by James A.R. Nafziger and Ann M. Nicgorski, 169-183. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2009.

b. Court decisions

- Tribunale Amministrativo Regionale del Lazio (Sez. II-quarter), February 28, 2007, No. 3518, Associazione nazionale Italia Nostra Onlus c. Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali et al.

- Consiglio di Stato, June 23, 2008, No. 3154, Associazione nazionale Italia Nostra Onlus c. Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali et al.

c. Legislation

- Decree of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities of 1 August 2002, published in Gazzetta Ufficiale No. 190 of 14 August 2002.

d. Documents

- Joint Communiqué between Italy and Libya of 4 July 1998.

e. Media

- “Libya Says Italy Apologizes for Colonial Occupation,” BBC News, July 10, 1998. Accessed December 1, 2011, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/world/monitoring/130160.stm

- “Italy Seals Libya Colonial Deal,” BBC News, August 30, 2008. Accessed December 1, 2011, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/7589557.stm.

[1] The Ottoman State (or Turkey) occupied the Eastern part of North Africa as early as 1880. A. Laroui, “African Initiatives and Resistance in North Africa and the Sahara”, in General History of Africa, VII, Africa under Colonial Domination 1880-1935, ed. Albert Adu Boahen (Paris: UNESCO, 1985), 94-100.

[2] Nancy C. Wilkie, “Colonization and Its Effect on the Cultural Property of Libya,” in Cultural Heritage Issues: The Legacy of Conquest, Colonization, and Commerce, ed. James A.R. Nafziger and Ann M. Nicgorski (Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2009), at 170-171.

[5] Tribunale Amministrativo Regionale del Lazio (Sez. II-quarter), 28 February 2007, No. 3518, Associazione nazionale Italia Nostra Onlus c. Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali et al.

[6] Consiglio di Stato, 23 June 2008, No. 3154, Associazione nazionale Italia Nostra Onlus c. Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali et al.

[7] “Italy Seals Libya Colonial Deal”, BBC News, August 30, 2008, accessed December 1, 2011, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/7589557.stm.

[8] Leaving aside illegal immigration, it should be recalled that, soon after Colonel Gheddafi’s rise to power in 1969, all Italians were expelled from the country and their property were confiscated, whereas, in 1986, Libya launched a missile which fell into waters close to Lampedusa in reprisal for the US bombing of Tripoli and Benghazi.

[9] For the English text of the 1998 Joint Communiqué see “Libya Says Italy Apologizes for Colonial Occupation”, BBC News, July 10, 1998, accessed December 1, 2011, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/world/monitoring/130160.stm.

[11] The Italian text of the decree was published in Gazzetta Ufficiale No. 190 of 14 August 2002.

[12] Tribunale Amministrativo Regionale del Lazio (Sez. II-quarter), 28 February 2007, No. 3518.

[13] For the English text of the 1998 Joint Communiqué see “Libya Says Italy Apologizes for Colonial Occupation”.

[14] “Italy Seals Libya Colonial Deal”, BBC News, August 30, 2008, accessed December 1, 2011, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/7589557.stm.

[15] See, e.g., Raphael Contel, Giulia Soldan, Alessandro Chechi, “Case Euphronios Krater and Other Archaeological Objects – Italy and Metropolitan Museum of Art,” Platform ArThemis (http://unige.ch/art-adr), Art-Law Centre, University of Geneva.

[16] Alessandro Chechi, “The Return of Cultural Objects Removed in Times of Colonial Domination and International Law: The Case of the Venus of Cyrene,” Italian Yearbook of International Law (2008): 160-174.

[17] See supra note 2 and related text.

[18] Natalino Ronzitti, “Sugli obblighi di restituzione la sentenza amministrativa non convince,” Guida al diritto-Il Sole 24 Ore 21 (2007): 100.

Document Actions