- Keywords

- Ownership/propriété, Illicit exportation/exportation illicite, Judicial decision/décision judiciaire, Iran, Unconditional restitution/restitution sans condition, Enforcement of foreign law/applicabilité du droit public étranger, Archaeological object/objet archéologique, The Barakat Galleries Ltd., Choice of law/droit applicable, Judicial claim/action en justice, Illicit excavation/fouille illicite, Procedural issue/limites procédurales, Post 1970 restitution claims/demandes de restitution post 1970

Jiroft Collection – Iran v. Barakat Galleries

|

|

|---|

DOWNLOAD AS PDF – CASE NOTE IN ENGLISH

TELECHARGER LE PDF – AFFAIRE EN FRANCAIS

Citation: Alessandro Chechi, Raphael Contel, Marc-André Renold, “Case Jiroft Collection – Iran v. The Barakat Galleries Ltd.,” Platform ArThemis (http://unige.ch/art-adr), Art-Law Centre, University of Geneva.

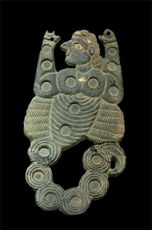

The Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran sued the London-based Barakat Galleries seeking the restitution of a collection of eighteen carved jars, bowls and cups which had been illicitly excavated in the Jiroft region, in Southeast Iran, and subsequently exported abroad. The Court of Appeal, overruling the trial court decision, held that the relevant laws of Iran were sufficiently clear to vest ownership title and an immediate right of possession of the relics in the Iranian State. Accordingly, the Court ruled that the lawsuit could be maintained. In this respect, the Court affirmed that the Iranian claim should not be shut out on the ground of the principle that domestic courts should not entertain legal actions brought by foreign sovereigns to enforce, directly or indirectly, its penal, revenue, or other public laws. Although it concerned the preliminary issue as to whether the claim was maintainable, the appeal decision is important for Iran in its bid to obtain the return of the contested artefacts.

I. Chronology

Post 1970 restitution claims

- 2006: The Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran demanded the London-based Barakat Galleries Ltd. (“Barakat”) the restitution of a collection of eighteen carved jars, bowls and cups. Iran alleged that these objects had been recently unlawfully excavated in the Jiroft region of Iran. Barakat refused.

- 2007: The Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran sued in conversion[1] Barakat seeking an order for the delivery up of such a collection. The claimant asserted that the antiquities had been taken in violation of its national ownership law given that, under Iranian law, the only owner of all antiquities – including those excavated in the Jiroft area which are the subject of the case at issue – is the Iranian State.

- 29 March 2007: Gray J, of the High Court of London, dismissed the claim on the ground that Iran had not discharged the burden of establishing its ownership of the collection under Iranian laws and hence it had no title to sue in conversion.[2] The Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran appealed the decision by arguing that the judge failed to recognise that Iran had ownership title to the antiquities and hence the right to recover them. Alternatively, the appellant contended that its immediate right to possession of the antiquities could found a claim for conversion or wrongful interference with goods.

- 21 December 2007: The Court of Appeal reversed the decision of Gray J and maintained the appellant’s claim for conversion.[3] The Court held that the relevant laws of Iran were sufficiently clear to vest ownership and an immediate right of possession of the relics in the Iranian State so as to enable it to bring an action for conversion in the English court. Furthermore, it affirmed that the Iranian claim to recover the antiquities, which formed part of its cultural heritage, should not be shut out on the ground that domestic courts should not entertain legal actions brought by foreign sovereigns to enforce its penal, revenue, or other public laws.

- 30 June 2008: the House of Lords rejected Barakat’s application to appeal the Court of Appeals decision.

II. Dispute Resolution Process

Judicial claim – Judicial decision

- This case revolved around the question of the ownership of a collection of antiquities dating from the period 3000 BC to 2000 BC that originated, allegedly, from recent clandestine excavations in the Jiroft region, and that had been illegally exported between 2000 and 2004. The origin of the antiquities was contested by the respondent. Nevertheless, the fact that Iranian law was the applicable law (lex situs) for the acquisition and transfer of title to the antiquities and that the antiquities originated from Iran was assumed to be correct for the purpose of the trial of the following preliminary issues: (i) whether Iran could show that it had obtained title to the relics as a matter of Iranian law and, if so, by what means; (ii) if Iran could show that it had obtained such title under Iranian law, whether the court should recognise and/or enforce that title.[4]

- The parties had made no attempt to settle the case out-of-court. A judicial decision by a court of law appeared to be the proper method of dispute settlement to adjudicate this claim involving ownership rights. In this respect, both Iran and Barakat submitted evidence in support of their claims.

- On the one hand, Iran attempted to demonstrate that Iranian law vested in Iran a proprietary title to the antiquities and entitled Iran to recover them through proceedings in England. Alternatively, it was asserted that Iranian law gave Iran an immediate right of possession of the antiquities that founded a claim in England for conversion or wrongful interference with the goods. Both the High Court and the Court of Appeal examined the pertinent legislation and decided what its effect was by testing the expert evidence against its language and context.[5] Crucially, the Court analysed Iranian legislation by adopting two principles of statutory interpretation: “statutes should be given a purposive interpretation and special provisions dealing with antiquities take precedence over general provisions”.[6]

- On the other hand, the Barakat sought to prevent any encroachment of its rights under the general law of possession and ownership. The defendant maintained that it had purchased the antiquities at auction or from other dealers in England, France, Germany and Switzerland under laws which have given it good title to them.[7] Barakat further maintained that, even if Iran was the legitimate owner of the antiquities, its claim should fail on grounds of non-justiciability as English courts have no jurisdiction to entertain actions for the enforcement of the penal, revenue or other public law of a foreign State.

III. Legal Issues

Illicit excavation – Illicit exportation – Ownership – Choice of law – Enforcement of foreign law – Procedural issue

- The central legal issue at stake in the instant case was the problem of the recognition of foreign heritage laws. The justiciability of the plaintiff’s claim depended on the resolution of this particular issue.

- Source nations have attempted to curb illicit trafficking in movable cultural materials through the enforcement of specific legislation. Although these laws vary between countries, they tend to take two forms. First, there are the patrimony laws that provide that ownership of certain categories of cultural objects is vested ipso iure in the State. Second, there are norms prohibiting or restricting the export of cultural materials. The formal distinction between patrimony laws and export regulations is critical because only the former category enjoys extraterritorial effect. On the contrary, a State is not obliged to recognize or enforce the export regulations of another State. In the absence of inter-State agreements, the domestic norms prohibiting or restricting the export of cultural materials are not enforced in foreign States. In other words, although source nations can legitimately enact export control laws, they cannot create an international obligation for market nations to recognize or enforce those measures.

- The distinction between patrimony laws and export regulations is blurred. This is due to the fact that art-rich States may construe their export laws as ownership laws in order to receive the assistance of foreign States. However, a simple declaration on the part of the requesting State does not suffice. The forum judge is called on to characterize the claim by scrutinizing the nature and wording of the national legislation at stake and, hence, he may or may not choose to adopt the characterization advocated by the claimant.

- Before the decision of the Court of Appeal in the instant case, the prevailing principle in England was that domestic courts had no jurisdiction to entertain an action for the enforcement, either directly or indirectly, of penal, revenue or other public law of a foreign State.[8] The reluctance of English courts to accept the extraterritoriality of these types of foreign laws was traditionally exemplified by the Ortiz case.[9] In this case, Lord Denning, from the Court of Appeal, asserted (obiter) that, by virtue of international law, no State had sovereignty beyond its own frontiers and, hence, no court would enforce foreign laws so as to allow a foreign State to exercise such sovereignty beyond the limits of its authority. He further explained that the category “other public laws” had to be understood to include the legislation prohibiting the export of works of art.[10]

- Such reluctance contrasts with the fact that most countries have adopted specific legislation protecting the national patrimony and hence they would benefit from the reciprocal enforcement of protective laws. Noticeably, the reluctance to enforce foreign public laws also contrasts with Article 13(d) 1970 UNESCO Convention, which obliges the States Parties, “consistent with the laws of each State”, “to recognize the indefeasible right of each State Party to this Convention to classify and declare certain cultural property as inalienable which should therefore ipso facto not be exported, and to facilitate recovery of such property by the State concerned in cases where it has been exported”.

- The Court of Appeal departed from the Ortiz precedent by stating that the appellant sought to assert an ownership right (“a patrimonial claim”) and not to enforce a public law or to assert sovereign rights.[11] In other words, the Court distinguished between recognition of a nation’s ownership rights and enforcement of a foreign nation’s laws. To do so, the Court recalled that under English conflict of laws principles the transfer of title to tangible movable property depends on the lex situs, that is, the law of the country where the movable was situated at the time of the transfer.[12] Therefore, if a State has acquired title to property situated within its jurisdiction, there is no reason why an English court should not recognize it. The same would apply where domestic laws provide that ownership of cultural objects is vested in the State without the need to have taken actual possession.

- With respect to the issue of ownership, the Court found that under the Iranian Law of 1979 (which superseded the provisions of earlier sources, such as the Civil Code of 1928, the National Heritage Protection Act of 1930 and the Regulations of 1932) “no one enjoys any rights in relation to antiquities found accidentally or as a result of illegal excavation except Iran and the rights that Iran enjoys are essentially the rights of ownership”.[13] As a result, the Court concluded that Gray J “was wrong to find that under Iranian law Iran had not shown that it was the owner”.[14]

IV. Adopted Solution

Unconditional restitution

- The preliminary issues before the High Court and the Court of Appeal were (i) whether Iran could show that it had a sufficient title to sue in conversion, and if so (ii) whether the Court should recognize and enforce that title for the purpose of admitting a claim in conversion against the defendant.

- The Court of Appeal first noted that Gray J had concluded that: (i) Iran had not discharged the burden of establishing its legal ownership of the antiquities; (ii) consequently, Iran had no title to sue in conversion;[15] (iii) the relevant Iranian legislation was both penal and public in character;[16] and (iv), as a result, could not be enforced by English courts.[17]

- The Court of Appeal dismissed this ruling. Their Lordships affirmed that whether a foreign law, or a claim based on foreign law, was to be characterized as penal depended on English law: “it is important to bear in mind that it is not the label which foreign law gives to the legal relationship, but its substance, which is relevant. If the rights given by Iranian law are equivalent to ownership in English law, then English law would treat that as ownership for the purposes of the conflict of laws”.[18] As a result, the Court affirmed that Iran’s “rights in relation to antiquities found were so extensive and exclusive that Iran was properly to be considered the [only] owner of the properties found”.[19] In other words, Their Lordships concluded that Iran enjoyed both title and an immediate right to possession of the antiquities which of itself sufficed to found a claim in conversion.[20]

- As to the questions whether the claim was founded on a penal or public law and whether it could be recognised or enforced by English courts, the Court classified the claim as a “patrimonial claim, not a claim to enforce a public law or to assert sovereign rights”.[21] In effect, Iran advanced a claim that was based upon a title that was conferred by legislation (and not acquired by confiscation or compulsory process). It is for this reason that Iran needed not to have taken actual possession of the relics.[22] The Court also held that “when a State owns property in the same way as a private citizen there is no impediment to recovery”.[23] Therefore, the Court of Appeal affirmed that English courts should recognize Iran’s national ownership law in order to allow Iran to sue to recover its antiquities.[24]

V. Comment

- With this ground-breaking decision, the Court of Appeal recognised Iran’s title in order to maintain Iran lawsuit. However, this decision is noteworthy because the Court did not stop here. It represents a tremendous gain for source countries because it went on to affirm that even if Iran had claimed the enforcement of its protective “public laws”, English courts were not barred from enforcing such laws, unless it was against public policy.[25] The Court affirmed: “There are positive reasons of policy why a claim by a State to recover antiquities which form part of its national heritage [...] should not be shut out […]. Conversely, [...] it is certainly contrary to public policy for such claims to be shut out. […] There is international recognition that States should assist one another to prevent the unlawful removal of cultural objects including antiquities”.[26] The Court briefly examined the international instruments which had the purpose of preventing unlawful dealing in property which is part of the cultural heritage of States (the 1970 UNESCO Convention, the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention, Directive 93/7, and the Commonwealth Scheme for the Protection of the Material Cultural Heritage of 1993) and asserted that “[n]one of these instruments directly affects the outcome of this appeal, but they do illustrate the international acceptance of the desirability of protection of the national heritage. A refusal to recognise the title of a foreign State, conferred by its law, to antiquities unless they had come into the possession of such State, would in most cases render it impossible for this country to recognise any claim by such a State to recover antiquities unlawfully exported to this country”.[27] Hence, the court affirmed that it is British public policy to recognize the ownership claim of foreign nations to antiquities that belong to their patrimony. Accordingly, although it concerned the preliminary issue as to whether the claim was maintainable, this decision established a clear precedent allowing source countries to bring legal claims in English courts when art objects appear for sale in the United Kingdom as a result of violations of domestic patrimony laws.

- The appeal decision of the Barakat case brought English law into line with the jurisprudence of the United States. The courts of the United States have recognized several times the ownership title of foreign States to clandestinely excavated cultural materials, even where States never had possession. In the most recent case, United States v. Schultz[28] (which was referred to by the Court of Appeal), an art dealer was convicted of conspiracy to receive property stolen in Egypt. The New York Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit interpreted the pertinent Egyptian law, which declared all antiquities found in Egypt after 1983 to be the property of the Egyptian Government, as an ownership law. As a result, the Court cleared the way for US courts to hear claims founded on foreign laws.

- Cases such as Schultz and Barakat demonstrate that the implementation of domestic norms has gradually evolved in the sense of allowing the restitution of art objects wrongfully removed from, and claimed back by, source countries, even in the absence of ownership title. This does not mean that theft and illegal exportation, on the one hand, and patrimony laws and export rules, on the other hand, are no longer differentiated. Rather, it means that situations with a connection to a status similar to ownership are increasingly recognized and deemed worthy of protection by the courts of England and the United States.

- Finally, it is worth underlining that the instant case is significant for it recognises the fundamental problem of the exportation of undocumented objects removed from illicit digs by clandestine excavators. It can be argued that the Court of Appeal adhered to the notion of “constructive” possession of antiquities. As no government can police every archaeological site in its country in an attempt to keep away looters, nor can it monitor every border crossing to enforce export controls, it must be admitted that States can establish and assert ownership through statutory provisions.[29]

VI. Sources

a. Bibliography

- Gerstenblith, Patty “Schultz and Barakat: Universal Recognition of National Ownership of Antiquities.” Art Antiquity and Law 1 (2009): 21-48.

b. Court decisions

- Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran v. The Barakat Galleries Ltd. [2007] EWHC 705 QB.

- Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran v. The Barakat Galleries Ltd. [2007] EWCA Civ. 1374, [2008] 1 All ER 1177.

c. Legislation

- Iran, Legal Bill on the Prevention of Unauthorised Excavations and Diggings, 17 May 1979.

[1] In Common Law “conversion” is a tort of strict liability that can be committed innocently “dealing with goods in a manner inconsistent with the rights of true owner” (Lancashire & Yorkshire v. MacNicoll [1919] 88 LJKB). This gives the true owner the right to sue for his/her own property or the value and loss of use of it, as well as going to law enforcement authorities since conversion usually includes the crime of theft (see at http://dictionary.law.com/).

[2] Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran v. The Barakat Galleries Ltd. [2007] EWHC 705 QB.

[3] Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran v. The Barakat Galleries Ltd. [2007] EWCA Civ. 1374.

[4] Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran v. The Barakat Galleries Ltd. [2007] EWHC 705 QB, paras. 4-5.

[5] Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran v. The Barakat Galleries Ltd. [2007] EWCA Civ. 1374, para. 50.

[7] Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran v. The Barakat Galleries Ltd. [2007] EWHC 705 QB, paras. 2, 10.

[8] Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran v. The Barakat Galleries Ltd. [2007] EWCA Civ. 1374, paras. 95 ff.

[9] Attorney General of New Zealand v. Ortiz [1982] 3 QB 432, rev’d, [1984] A.C. 1, add’d, [1983] 2 All E.R. 93.

[10] Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran v. The Barakat Galleries Ltd. [2007] EWCA Civ. 1374, paras. 104 ff. and 112 ff.

[15] Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran v. The Barakat Galleries Ltd. [2007] EWHC 705 QB, paras. 59, 70-71.

[18] Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran v. The Barakat Galleries Ltd. [2007] EWCA Civ. 1374, paras. 49, 106.

[22] Ibid., para. 131. On the contrary, the State has to reduce the property to possession while the property is still located within the State if ownership is acquired through compulsory process or confiscation. If the foreign State has not obtained possession first and the property has been transferred abroad, it means that that State is asking the foreign court to enforce its penal law.

[28] United States v Schultz, 178 F. Supp. 2d 445 (S.D.N.Y. 2002), aff’d, 333 F 3d 393 (2d Cir. 2003).

[29] On this point see Patty Gerstenblith, “Schultz and Barakat: Universal Recognition of National Ownership of Antiquities,” Art Antiquity and Law 1 (2009): 46.

Document Actions