Banksy Mural – Bioresource, Inc. and 555 Nonprofit Studio/Gallery

|

|

|---|---|

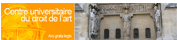

| The removal of the Banksy Mural - Boston Herald | Banksy Mural - Canary in a Cage - Detroit Free Press |

DOWNLOAD AS PDF – CASE NOTE IN ENGLISH

TELECHARGER LE PDF – AFFAIRE EN FRANCAIS

Citation: Anne Laure Bandle, Andrea Wallace, Marc-André Renold, “Case Banksy Mural – Bioresource, Inc. and 555 Nonprofit Studio/Gallery,” Platform ArThemis (http://unige.ch/art-adr), Art-Law Centre, University of Geneva.

Artists from the 555 Nonprofit Studio/Gallery removed an endangered mural painting by the graffiti artist Banksy from a derelict site in Detroit. The owner of the site, Bioresource, Inc. subsequently filed suit with the Wayne County Circuit Court requesting the wall art’s restitution. The parties finally settled their dispute as the Company agreed to donate the mural to the Gallery, who paid the Company a symbolic amount.

I. Chronology

- May 2010: Artists from the 555 Nonprofit Studio/Gallery (hereafter the Gallery) in the City of Detroit removed the mural painting “I remember when all this was trees” by renowned English street artist Banksy. The mural was cut from a dilapidated site in Detroit where it had been affixed to a cinder-block wall on Detroit property known as the “Packard Motor Plant”. By doing so, the artists wished to protect the artwork from impending demolition. Following its removal, the wall art was placed on free public display at the Gallery.

- 7 June 2010: Bioresource, Inc., a technology company owning the Packard site (hereafter the Company), asked the Gallery to return the painting, asserting that it had been removed without its consent.

- July 2010: As its request was unsuccessful, the Company sued the Gallery at the Wayne County Circuit Court to reclaim possession of the artwork[1].

- August 2010: In a motion for possession hearing pending judgment on the case, the Wayne County Circuit Court ruled that the mural should remain with the Gallery[2].

- April 2012: Despite the fact that the claimant argued the wall art’s worth to be $100,000, if not more, the Gallery and the plant owner settled the case for $2,500, which was provided by gallery supporters. Upon its return to the Gallery, the work was placed on public display on 27 April, but not for sale[3].

II. Dispute Resolution Process

Judicial claim – Negotiation – Settlement agreement

- Pending its judicial decision, the Wayne District Court allowed the Gallery’s temporary possession of the wall art. Thereby, the mural would be secured from being destroyed or sold at the Gallery[4]. Finally, the parties managed to settle their case before the beginning of the trial.

- The negotiations enabled each party to present its interests in this dispute. In particular, it seems that a misunderstanding as to the Gallery’s motivation for retrieving the wall art had precipitated the plant owner’s lawsuit. The plant owner believed the artists removed the painting in order to sell it, given the considerable market value for Banksy’s art. In response, the Gallery’s director pointed out that the mural had been on one of the last walls standing within a large area of debris’. Therefore, their sole intention had been to protect it. Moreover, they had believed that they were permitted to do so[5].

III. Legal Issues

Ownership

- The lawsuit over the Banksy mural focused on the issue of the mural’s ownership[6]. The Company brought a conversion claim, arguing that the mural painting was located on its property prior to the Gallery’s wrongful removal and control of the wall art. The tortious removal of property annexed to a freehold constitutes an act of conversion[7]. While the artists’ and the Gallery’s good faith may not been a proper affirmative defence to conversion, they could have argued the doctrine of abandonment[8]. Considering that the mural painting was attached to one of the last standing walls of the derelict Plant, a building which city officials were urging for demolition, the defendants could have argued the owner had not manifested any intention to use or retain ownership of the property containing the wall art[9]. Besides, the artists were presumably given permission to take the wall art by the scrap metal removal workers’ foreman working for the Company owner on the site[10].

- An additional property-related issue could have arisen in determining whether Banksy or the artists had trespassed by accessing the Company’s property without permission[11]. Even so, both the artists and Banksy could have responded by a tenable defence. While the Company owned the perimeter, it had neither fenced off nor guarded the Plant to protect it from the many visiting explorers, tourists, and vandals[12]. Thus, in theory, the Company might have consented to a public easement, which would have allowed public access to the Plant, excluding any action of trespass[13].

IV. Adopted Solution

Donation – Symbolic gesture

- The Gallery received clear title to the Banksy mural as part of a settlement reached with Bioresource Inc. In return, the Gallery paid $2,500 to the company.

V. Comment

- Shortly after the controversy over the Bansky mural painting had erupted, the Company discovered a second mural painting by the same artist on the Packard Plant, depicting a yellow canary in a cage. The mural was also removed, but this time by the plant owner’s agents[14]. Later, it was put up for sale on eBay, but failed to attract a bid high enough to meet the reserve price[15]. The actual whereabouts of the second mural remain unclear[16].

- The removal of the street art from its original context may raise authenticity issues as the creators could disavow work that is retrieved or altered from its original state[17]. Moreover, it could violate the creator’s intent for the work to remain publicly accessible since it is produced in public spaces, as opposed to works intended to be sold on the market and privately owned. The street artist Ben Eine, who has collaborated with Banksy for many years, said that street art is “not made to be sold, but to be enjoyed”[18].

- The question also remains as to whether the work’s copyright holders could validly assert that its display and sale violates their exclusive rights under 17 U.S.C. § 106(3) and (5). Under the first sale doctrine, the owner of a work may validly sell or exhibit a work after its initial sale by the copyright owner, but the situation is less clear regarding works “abandoned” by their copyright owners. Some have argued that the doctrine should not be restricted to sales, but extended to all transfers of ownership. This extension would allow the right of first distribution, e.g. the right to control the first public distribution of the work, and include the abandonment of ownership[19]. Applying this doctrine to the present case, Banksy would have exercised his right of first distribution when he relinquished ownership of the wall paintings in a way that would demonstrate an intent to release them to others[20]. Thus, he would be prevented from interfering with their sale or display.

VI. Sources

a. Bibliography

- Karmel, Dan. “Off the Wall: Abandonment and the First Sale Doctrine.” NYIPLA Bulletin (October/November 2012): 1, 3 – 12. Accessed July 26, 2013. http://www.nyipla.org/images/nyipla/Documents/Bulletin/2012/OctoberNovember2012.pdf.

b. Documents

- Video of the mural’s removal: See Stryker, Mark. “Detroit gallery hides Banksy's graffiti art after threats.” Detroit Free Press, May 29, 2010. Accessed July 26, 2013. http://www.freep.com/article/20100529/ENT05/305290005/Detroit-gallery-hides-Banksy-s-graffiti-art-after-threats.

c. Media

- "Banksy's No Ball Games mural removed from Tottenham wall." BBC News, July 26, 2013. Accessed July 26, 2013. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-23461396.

- Wetherbe, Jamie. “Salvaged Banksy artwork goes on display in Detroit.” Los Angeles Times, April 27, 2012. Accessed July 26, 2013. http://articles.latimes.com/2012/apr/27/entertainment/la-et-cm-banksy-mural-debuts-in-detroit-gallery-20120426.

- Shaw, Anny. “Banksy Murals Prove to be an Attribution Minefield.” The Art Newspaper, February, 16, 2012. Accessed July 26, 2013. http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/Banksy-murals-prove-to-be-an-attribution-minefield/25631.

- Stryker, Mark. “555 Gallery gets OK to display Banksy mural.” Detroit Free Press, September 11, 2011. Accessed July 26, 2013. http://www.freep.com/article/20110910/ENT05/103020001/555-Gallery-gets-OK-display-Banksy-mural.

- Stryker, Mark, Tresa Baldas and Gina Damron. “Banksy Mural Stays in Gallery Until June Trial.” Detroit Free Press, September 2, 2010, A6.

- Stryker, Mark. “2nd Banksy work leaves Packard.” Detroit Free Press, June 18, 2010. Accessed July 26, 2013. http://www.freep.com/article/20100618/ENT05/6180307/2nd-Banksy-work-leaves-Packard.

- Stryker, Mark. “Detroit gallery hides Banksy's graffiti art after threats.” Detroit Free Press, May 29, 2010. Accessed July 26, 2013. http://www.freep.com/article/20100529/ENT05/305290005/Detroit-gallery-hides-Banksy-s-graffiti-art-after-threats.

- Cowley, Stacy. “The Holdout: Alone in an Abandoned Car Plant.” CNNMoney.com, October 30, 2009. Accessed July 26, 2013. http://money.cnn.com/2009/10/30/smallbusiness/chemical_processing_detroit.smb/index.htm.

- Stryker, Mark. “2nd Banksy Work Leaves Packard,” Detroit Free Press, June 18, 2010, at A2.

[1] Bioresource, Inc., v. 555 Nonprofit Studio/Gallery, Wayne County Circuit Court, July 6, 2010 (complaint).

[2] See Dan Karmel, “Off the Wall: Abandonment and the First Sale Doctrine,” NYIPLA Bulletin (October/November 2012): 3, accessed July 26, 2013, http://www.nyipla.org/images/nyipla/Documents/Bulletin/2012/OctoberNovember2012.pdf.

[3] See Jamie Wetherbe, “Salvaged Banksy artwork goes on display in Detroit,” Los Angeles Times, April 27, 2012, accessed July 26, 2013, http://articles.latimes.com/2012/apr/27/entertainment/la-et-cm-banksy-mural-debuts-in-detroit-gallery-20120426.

[4] See Mark Stryker et al., “Banksy Mural Stays in Gallery Until June Trial,” Detroit Free Press, September 2, 2010, A6.

[5] See Mark Stryker, “555 Gallery gets OK to display Banksy mural,” Detroit Free Press, September 11, 2011, accessed July 26, 2013, http://www.freep.com/article/20110910/ENT05/103020001/555-Gallery-gets-OK-display-Banksy-mural; Wetherbe, “Salvaged Banksy artwork goes on display in Detroit.”

[6] Bioresource, Inc., v. 555 Nonprofit Studio/Gallery, Wayne County Circuit Court, July 6, 2010 (complaint).

[7] See Peiser v. Mettler, 50 Cal.2d 594 (Cal. Sup. Ct 1958), para. 15.

[8] See Rodgers v. Crum, 168 Kan. 668 (Kan. Sup. Ct. 1950).

[9] On the definition of abandonment, see United States v. Sinkler, 91 F. App’x 226, 231 (3rd Cir. 2004).

[10] See Mark Stryker, “Detroit gallery hides Banksy's graffiti art after threats,” Detroit Free Press, May 29, 2010, accessed July 26, 2013, http://www.freep.com/article/20100529/ENT05/305290005/Detroit-gallery-hides-Banksy-s-graffiti-art-after-threats.

[11] See Karmel, “Off the Wall: Abandonment and the First Sale Doctrine,” 11 fn. 27.

[12] See Stacy Cowley, “The Holdout: Alone in an Abandoned Car Plant,” CNNMoney.com, October 30, 2009, accessed July 26, 2013, http://money.cnn.com/2009/10/30/smallbusiness/chemical_processing_detroit.smb/index.htm.

[13] See Karmel, “Off the Wall: Abandonment and the First Sale Doctrine,” 11 fn. 27.

[14] See Mark Stryker, “2nd Banksy work leaves Packard,” Detroit Free Press, June 18, 2010, accessed July 26, 2013, http://www.freep.com/article/20100618/ENT05/6180307/2nd-Banksy-work-leaves-Packard.

[15] See Karmel, “Off the Wall: Abandonment and the First Sale Doctrine,” 3. Other Banksy murals have been removed from the walls by the owners of the buildings where they were located only to be sold at auction, see "Banksy's No Ball Games mural removed from Tottenham wall," BBC News, July 26, 2013, accessed July 26, 2013, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-23461396.

[16] See Stryker, “555 Gallery gets OK to display Banksy mural.”

[17] See Karmel, “Off the Wall: Abandonment and the First Sale Doctrine,” 3.

[18] Anny Shaw, “Banksy Murals Prove to be an Attribution Minefield,” The Art Newspaper, February, 16, 2012, accessed July 26, 2013, http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/Banksy-murals-prove-to-be-an-attribution-minefield/25631.

[19] See Karmel, “Off the Wall: Abandonment and the First Sale Doctrine,” 9.

[20] See Karmel, “Off the Wall: Abandonment and the First Sale Doctrine,” 10.

Document Actions