- Keywords

- Settlement agreement/accord transactionnel, Negotiation/négociation, Ad hoc facilitator/facilitateur ad hoc, Antiquity/antiquités, Mediation/médiation, Canton of Saint-Gall/Canton de Saint-Gall, Ownership/propriété, Spoils of war/butins de guerre, Canton of Zurich/Canton de Zurich, Copy/copie, Loan/prêt

- Documents

-

-

Mediation Agreement between the Cantons of Zurich and Saint-Gall, 27 April 2007

Mediation Agreement between the Cantons of Zurich and Saint-Gall, 27 April 2007

-

Anne Laure Bandle and Sarah Theurich, Alternative Dispute Resolution and Art Law, Journal of International Commercial Law and Technology

Anne Laure Bandle and Sarah Theurich, Alternative Dispute Resolution and Art Law, Journal of International Commercial Law and Technology

-

Confederation suisse communiqué de presse - Fin du litige sur des biens culturels entre St-Gall et Zurich grâce à la médiation de la Confédération, April 27, 2006

Confederation suisse communiqué de presse - Fin du litige sur des biens culturels entre St-Gall et Zurich grâce à la médiation de la Confédération, April 27, 2006

-

Case Note – Ancient Manuscripts and Globe – Saint-Gall and Zurich

Case Note – Ancient Manuscripts and Globe – Saint-Gall and Zurich

-

Fiche – Ancient Manuscrits et Globe – Saint-Gall et Zurich

Fiche – Ancient Manuscrits et Globe – Saint-Gall et Zurich

-

Ancient Manuscripts and Globe – Saint-Gall and Zurich

|

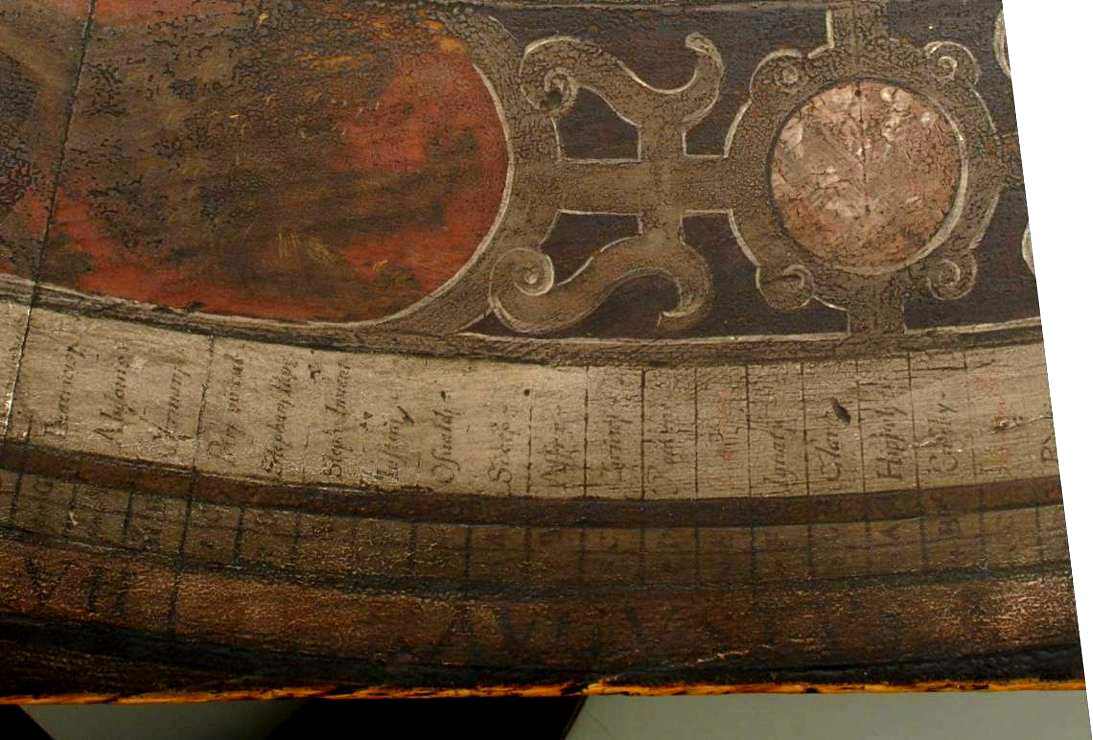

Frame with Names of the Saints - Original |

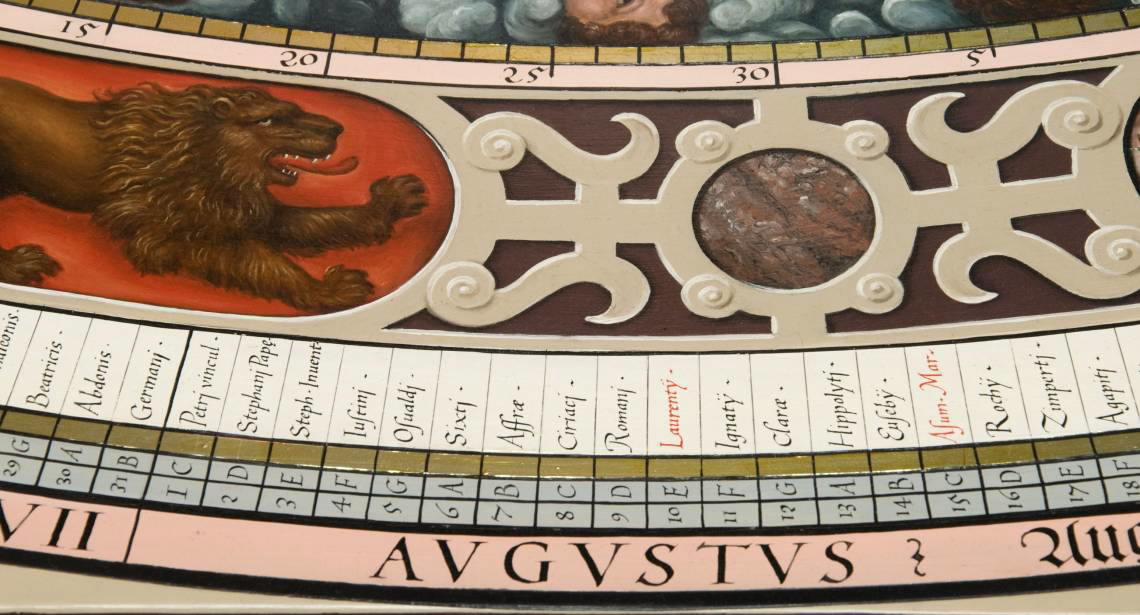

Frame with Names of the Saints - Copy |

|---|---|---|

| Copy of the Terrestrial Globe |

DOWNLOAD AS PDF – CASE NOTE IN ENGLISH

TELECHARGER LE PDF – AFFAIRE EN FRANCAIS

Citation: Anne Laure Bandle, Raphael Contel, Marc-André Renold, “Case Ancient Manuscripts and Globe – Saint-Gall and Zurich,” Platform ArThemis (http://unige.ch/art-adr), Art-Law Centre, University of Geneva.

Thanks to the Swiss Confederation who acted as a mediator, the dispute between the Cantons of Zurich and Saint-Gall over cultural objects displaced during the religious wars of 1712 was ultimately settled in 2006 by an inventive agreement.

I. Chronology

Spoils of war

- 1712: Religious wars between Catholic and Reformed Cantons – the so-called “Battles of Villmergen”. A number of cultural objects that previously belonged to the Abbey Library of Saint-Gall are transferred to Zurich.

- 15 June 1718: Peace Treaty between the Cantons of Saint-Gall and Zurich signed in Baden (hereafter the Peace Treaty of Baden). Zurich agrees to return most of the cultural objects taken from the Abbey of Saint-Gall, except for some 100 items, such as manuscripts, books, paintings, astronomical devices and the Prince-Abbot Bernhard Muller’s cosmographical Globe.

- 5 August 1718: Ratification of the Peace Treaty of Baden.[1] In the following years, the possibility of further returns was proffered by representatives on the Zurich side.[2]

- 1735: Further requests by Saint-Gall addressed to Zurich for the return of the remaining books and manuscripts and in particular of the Terrestrial and Celestial Globe. Zurich subsequently denied taking these objects.[3]

- 1996: Letter by a reader to the editor of a journal from Saint-Gall, claiming for the canton’s ownership of the cultural goods that had remained in the Central Library and National Museum in Zurich. The letter raised a public debate, which induced the involvement of the Cantonal Executive Council of Saint-Gall.

- Beginning of formal negotiations by a request from the Council of Saint-Gall to the Canton of Zurich for the return of the cultural goods. The claim was based on legal considerations, asserting that the objects had never been validly acquired by Zurich in view of the applicable federal law on war, which already prohibited the robbery of cultural goods. Zurich in turn insisted on its legitimate acquisition of property under the relevant international law provisions. Moreover, given the signed Peace treaty and the resultant restitution of objects, any claims would be forfeited or at least time-barred and therefore void.[4]

- After unsuccessful negotiations efforts, request by both parties for the Confederation’s intervention as a mediator in the dispute.

- 27 April 2006: (Public) Settlement agreement reached through mediation.[5]

II. Dispute Resolution Process

Ad hoc facilitator – Mediation – Negotiation – Settlement agreement

- The parties tried for eight years to negotiate their dispute – without success. It was only with the help of the Confederation acting as a mediator (as provided by the Swiss Constitution of 1999, art. 44 (3)) that the parties set aside their legal positions and instead focused on their mutual interests.

- A mediation-team assigned by the Swiss Government assisted in the settlement between political representatives from both Cantons and the responsible bodies of the concerned libraries.

III. Legal Issues

Ownership

- The two main considerations regarding the issue of ownership were:

- 1. On the property right transfers in the 18th century: have the parties purposely left out the remaining cultural objects in the Peace Treaty of Baden?

- Art. 81 of the Peace Treaty of Baden encloses an obligation to rescind all transfers of possession which occurred as a consequence of the war.[6] It does not, however, explicitly refer to the cultural objects. The opinions are divided between those asserting that a transfer of ownership to Zurich requires an agreement between the parties or a court decision and those alleging that all changes of property in favour of Saint-Gall have to be explicitly stated in the Peace Treaty.

- According to Schweizer/Hailbronner/Burmeister,[7] the circumstances and statements by the parties when signing the Peace Treaty and subsequent to their agreement suggest that they provided for the return of the cultural property objects. Saint-Gall for instance certified that the demand for restitution would not be dismissed, but put on hold until the ratification of the treaty.[8] The ratification of the Peace Treaty and subsequent return of a large amount of objects may be considered “the incomplete performance of a recognized duty”,[9] requiring the restitution of all objects. Saint-Gall on the other hand has never renounced the remaining objects; the Canton indeed repeatedly requested their restitution in the 18th and 19th centuries.[10]

- 2. On the actual ownership title of the cultural objects: Has the property title been validly transferred to Zurich or was Saint-Gall entitled to the restitution of all cultural objects? If so, is the restitution claim time-barred?

- Many of the international treaties recognizing the protection of illicitly taken cultural heritage in the event of armed conflict were not applicable to the battle of Villmergen (such as the Hague Convention of 1907[11] concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land (art. 23 (g); art. 27 and 56 of its annex) and the Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict (art. 4)[12] and its two protocols.[13] The main argument in favour of restitution is the consideration that the requested items are part of an ensemble which should remain together (cf. art. 69 (2) of the Swiss Constitution[14] requiring the Confederation to “support cultural activities of national interest”[15]), also in view of the designation of the Abbey Library of Saint-Gall as UNESCO World Cultural Heritage in 1982.[16] Therefore, it may well be argued that, in disregard of formal considerations such as limitation-periods, the restitution of these objects responds to international public law and to the interests of the Swiss Confederation.

IV. Adopted solution

Copy – Loan

- The mediation agreement provides the following settlement:

- Mutual acknowledgment: Saint-Gall accepts Zurich’s ownership of the cultural objects which are located at the National Museum and the Central Library in Zurich ever since the end of the war (art. 1). Zurich in return recognizes the importance of the objects for Saint-Gall’s cultural identity (art. 2).

- Loan: Zurich offers Saint-Gall an unpaid and indefinite loan regarding 35 manuscripts that belong to the Central Library Foundation in Zurich (art. 4). Moreover, Zurich has agreed to lend the original Cosmographical Globe to Saint-Gall to be exhibited for 4 months (art. 3). The exhibition of the manuscripts took place in September 2006 at the Abbey Library, which were in the following included in a special exhibition between December 2006 and February 2007.

- Copy: Zurich approved the production of an exact replica of the cosmographical Globe at its own expense and to donate it to Saint-Gall (art. 3). The original is kept at the Swiss National Museum. The replica was welcomed at the Abbey Library in Saint-Gall accompanied by a celebration in August 2009.

- Amendment or termination of the loan agreement: Any amendment or termination of the loan agreement can be made only after 38 years by a joint request from the highest executive of each party (art. 6-7).

V. Comment

- The Cantons probably failed in their negotiations as they were too entrenched in their legal positions, rather than focusing on a mutually beneficial plan.

- Interestingly, public pressure, particularly from the media has brought the issue back to the headlines. Only then did it become a concern for both cantons which apparently had forgotten about the matter long ago.

- Although both Saint-Gall and Zurich made considerable concessions (the copy of the Globe cost Zurich a great amount of money), some in Saint-Gall do not seem satisfied by the agreement,[17] claiming that the original Globe belongs to Saint-Gall and the Abbey Library would be a much better fit for its exhibition.

VI. Sources

a. Bibliography

- Bandle, Anne Laure, and Theurich, Sarah. “Alternative Dispute Resolution and Art-Law – A New Research Project of the Geneva Art-Law Centre.” Journal of International Commercial Law and Technology, Vol. 6, No. 1 (2011): 28 - 41.

- Schönenberger, Beat. The Restitution of Cultural Assets. Bern: Stämpfli Verlag AG, 2009.

- Schweizer, J. Rainer, Kay Hailbronner and Karl Heinz Burmeister. Der Anspruch von St. Gallen auf Rückerstattung seiner Kulturgüter aus Zürich. Zürich et al: Schulthess, 2002.

- Scovazzi, Tullio. “Diviser c’est détruire: Ethical Principles and Legal Rules in the Field of Return of Cultural Properties.” UNESCO, 2008.

b. Documents

- Mediation agreement between the Canton of Saint-Gall and the Catholic representative on the one hand, and the Foundation of the Central Library in Zurich as well as the Canton and City of Zurich on the other hand, April 27, 2006. Accessed October 2, 2011, http://www.news.admin.ch/NSBSubscriber/message/attachments/2567.pdf.

- Rohrbach, Martina, and Beat Gnädinger. Der Zürcher Globus. Projekt Globus-Replik 2007–2009, Dokumentation. Zürich: Staatsarchiv des Kantons, 2009. Accessed October 2, 2011, http://www.staatsarchiv.zh.ch/internet/justiz_inneres/sta/de/ueber_uns/veroeffentlichungen/_jcr_content/contentPar/downloadlist/downloaditems/download.spooler.download.1282816347217.pdf/Globus_Doku_1_0.pdf.

c. Media

- Lüscher, Geneviève. “Himmel und Erde.” Neue Zürcher Zeitung am Sonntag, February 14, 2010. Accessed October 2, 2011, http://www.nzz.ch/nachrichten/hintergrund/%20wissenschaft/himmel_und_erde_1.4954311.html.

- Eisenbeiss, Wolfgang. “Nachwehen im Streit um Himmelsglobus.” Neue Zürcher Zeitung, March 15, 2007. Accessed October 2, 2011, http://www.nzz.ch/2007/03/15/br/articleezp44_1.128067.html.

- Confédération suisse communiqué de presse. “Fin du litige sur des biens culturels entre St-Gall et Zurich grâce à la médiation de la Confédération.” April 27, 2006. Accessed October 2, 2011, http://www.staatsarchiv.zh.ch/internet/justiz_inneres/sta/de/ueber_uns/veroeffentlichungen/_jcr_content/contentPar/downloadlist/downloaditems/download.spooler.download.1282816347217.pdf/Globus_Doku_1_0.pdf.

- “250 mittelalterliche Handschriften online zugänglich.” Neue Zürcher Zeitung, January 26, 2006. Accessed October 2, 2011, http://www.nzz.ch/nachrichten/panorama/250_mittelalterliche_handschriften_online_zugaenglich__1.1786067.html.

[1] See Rainer J. Schweizer, Kay Hailbronner and Karl Heinz Burmeister, Der Anspruch von St. Gallen auf Rückerstattung seiner Kulturgüter aus Zürich (Zürich et al: Schulthess, 2002), 103.

[4] See Beat Schönenberger, The Restitution of Cultural Assets (Bern: Stämpfli Verlag AG, 2009), 10 et seq.

[5] Mediation agreement between the Canton of Saint-Gall and the Catholic representative on the one hand, and the Foundation of the Central Library in Zurich as well as the Canton and City of Zurich on the other hand, April 27, 2006, accessed October 2, 2011, http://www.news.admin.ch/NSBSubscriber/message/attachments/2567.pdf.

[6] See Schweizer et al., Der Anspruch von St. Gallen auf Rückerstattung seiner Kulturgüter aus Zürich, 93 et seq.

[11] Convention (IV) respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its annex: Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land. The Hague, 18 October 1907, accessed August 10, 2011, http://www.icrc.org/ihl.nsf/full/195.

[12] UNESCO Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, The Hague, 14 May 1954 (The Hague Convention of 1954), accessed August 10, 2011, http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13637&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html.

[13] Protocol to the Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed conflict 1954, The Hague 14 May 1954, accessed August 10, 2011, http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=15391&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC& URL_SECTION=201.html; Second Protocol to The Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict 1999, The Hague, 26 march 1999, accessed August 10, 2011, http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=15207&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201. html.

[14] Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation of April 18, 1999, SR 101, accessed August 10, 2011, http://www.admin.ch/ch/e/rs/1/101.en.pdf.

[15] It may be a national interest that cultural property is kept in its historical context and as an ensemble.

[16] See Schweizer et al., Der Anspruch von St. Gallen, 199 et seqq.; see also Tullio Scovazzi, “Diviser c’est détruire: Ethical Principles and Legal Rules in the Field of Return of Cultural Properties,” UNESCO, 2008.

[17] See Wolfgang Eisenbeiss, “Nachwehen im Streit um Himmelsglobus,” Neue Zürcher Zeitung, March 15, 2007, accessed October 2, 2011, http://www.nzz.ch/2007/03/15/br/articleezp44_1.128067.html.

Document Actions